The Big Hack: How China Used a Tiny Chip to Infiltrate U.S. Companies

The attack by Chinese spies reached almost 30 U.S. companies, including Amazon and Apple, by compromising America’s technology supply chain, according to extensive interviews with government and corporate sources.

In 2015, Amazon.com Inc. began quietly evaluating a startup called Elemental Technologies, a potential acquisition to help with a major expansion of its streaming video service, known today as Amazon Prime Video. Based in Portland, Ore., Elemental made software for compressing massive video files and formatting them for different devices. Its technology had helped stream the Olympic Games online, communicate with the International Space Station, and funnel drone footage to the Central Intelligence Agency. Elemental’s national security contracts weren’t the main reason for the proposed acquisition, but they fit nicely with Amazon’s government businesses, such as the highly secure cloud that Amazon Web Services (AWS) was building for the CIA.

To help with due diligence, AWS, which was overseeing the prospective acquisition, hired a third-party company to scrutinize Elemental’s security, according to one person familiar with the process. The first pass uncovered troubling issues, prompting AWS to take a closer look at Elemental’s main product: the expensive servers that customers installed in their networks to handle the video compression. These servers were assembled for Elemental by Super Micro Computer Inc., a San Jose-based company (commonly known as Supermicro) that’s also one of the world’s biggest suppliers of server motherboards, the fiberglass-mounted clusters of chips and capacitors that act as the neurons of data centers large and small. In late spring of 2015, Elemental’s staff boxed up several servers and sent them to Ontario, Canada, for the third-party security company to test, the person says.

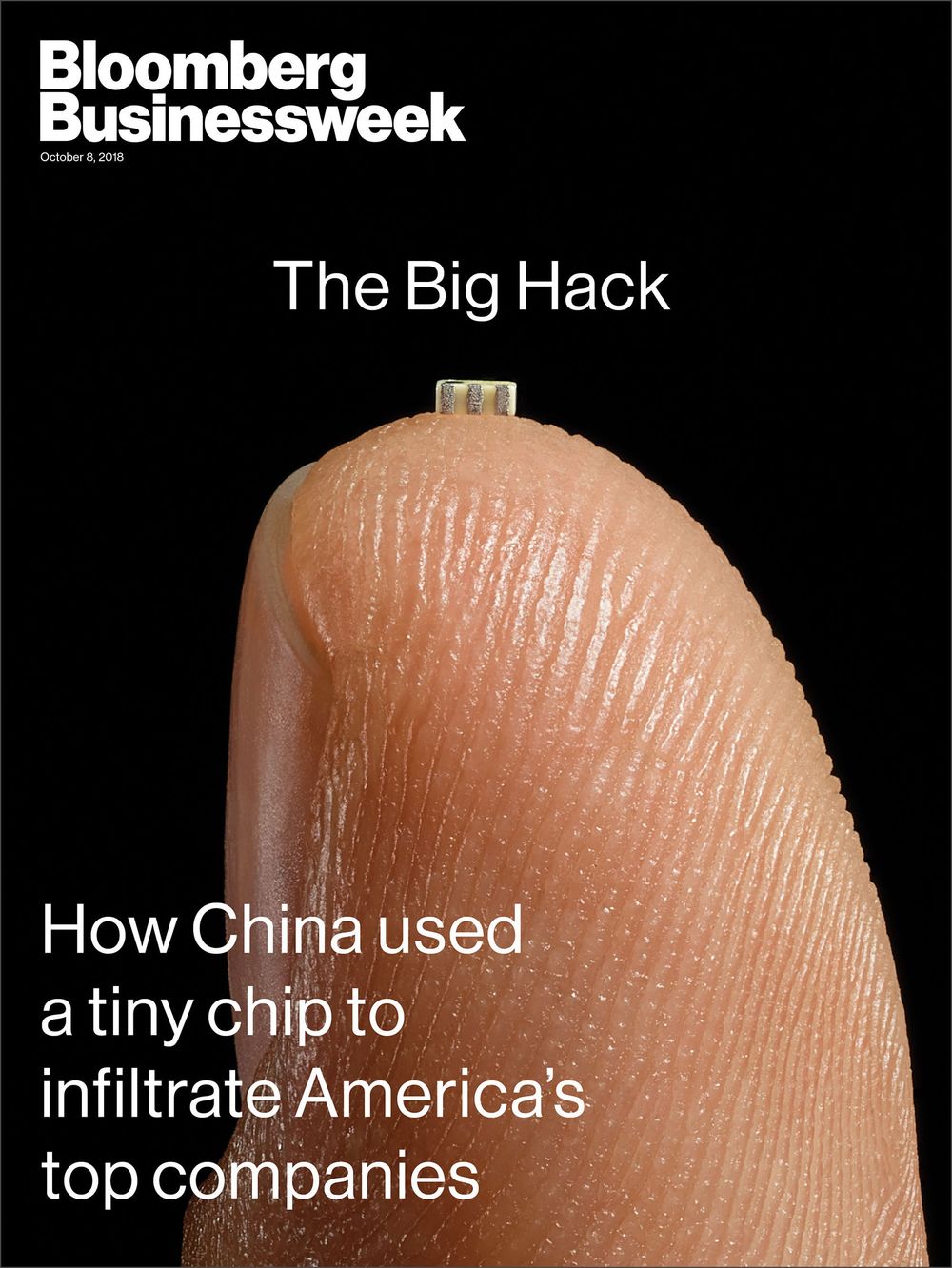

Nested on the servers’ motherboards, the testers found a tiny microchip, not much bigger than a grain of rice, that wasn’t part of the boards’ original design. Amazon reported the discovery to U.S. authorities, sending a shudder through the intelligence community. Elemental’s servers could be found in Department of Defense data centers, the CIA’s drone operations, and the onboard networks of Navy warships. And Elemental was just one of hundreds of Supermicro customers.

During the ensuing top-secret probe, which remains open more than three years later, investigators determined that the chips allowed the attackers to create a stealth doorway into any network that included the altered machines. Multiple people familiar with the matter say investigators found that the chips had been inserted at factories run by manufacturing subcontractors in China.

This attack was something graver than the software-based incidents the world has grown accustomed to seeing. Hardware hacks are more difficult to pull off and potentially more devastating, promising the kind of long-term, stealth access that spy agencies are willing

to invest millions of dollars and many years to get.

“Having a well-done, nation-state-level hardware implant surface would be like witnessing a unicorn jumping over a rainbow”

There are two ways for spies to alter the guts of computer equipment. One, known as interdiction, consists of manipulating devices as they’re in transit from manufacturer to customer. This approach is favored by U.S. spy agencies, according to documents leaked by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden. The other method involves seeding changes from the very beginning.

One country in particular has an advantage executing this kind of attack: China, which by some estimates makes 75 percent of the world’s mobile phones and 90 percent of its PCs. Still, to actually accomplish a seeding attack would mean developing a deep understanding of a product’s design, manipulating components at the factory, and ensuring that the doctored devices made it through the global logistics chain to the desired location—a feat akin to throwing a stick in the Yangtze River upstream from Shanghai and ensuring that it washes ashore in Seattle. “Having a well-done, nation-state-level hardware implant surface would be like witnessing a unicorn jumping over a rainbow,” says Joe Grand, a hardware hacker and the founder of Grand Idea Studio Inc. “Hardware is just so far off the radar, it’s almost treated like black magic.”

But that’s just what U.S. investigators found: The chips had been inserted during the manufacturing process, two officials say, by operatives from a unit of the People’s Liberation Army. In Supermicro, China’s spies appear to have found a perfect conduit for what U.S. officials now describe as the most significant supply chain attack known to have been carried out against American companies.

One official says investigators found that it eventually affected almost 30 companies, including a major bank, government contractors, and the world’s most valuable company, Apple Inc. Apple was an important Supermicro customer and had planned to order more than 30,000 of its servers in two years for a new global network of data centers. Three senior insiders at Apple say that in the summer of 2015, it, too, found malicious chips on Supermicro motherboards. Apple severed ties with Supermicro the following year, for what it described as unrelated reasons.

In emailed statements, Amazon (which announced its acquisition of Elemental in September 2015), Apple, and Supermicro disputed summaries of Bloomberg Businessweek’s reporting. “It’s untrue that AWS knew about a supply chain compromise, an issue with malicious chips, or hardware modifications when acquiring Elemental,” Amazon wrote. “On this we can be very clear: Apple has never found malicious chips, ‘hardware manipulations’ or vulnerabilities purposely planted in any server,” Apple wrote. “We remain unaware of any such investigation,” wrote a spokesman for Supermicro, Perry Hayes. The Chinese government didn’t directly address questions about manipulation of Supermicro servers, issuing a statement that read, in part, “Supply chain safety in cyberspace is an issue of common concern, and China is also a victim.” The FBI and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, representing the CIA and NSA, declined to comment.

Related:

The companies’ denials are countered by six current and former senior national security officials, who—in conversations that began during the Obama administration and continued under the Trump administration—detailed the discovery of the chips and the government’s investigation. One of those officials and two people inside AWS provided extensive information on how the attack played out at Elemental and Amazon; the official and one of the insiders also described Amazon’s cooperation with the government investigation. In addition to the three Apple insiders, four of the six U.S. officials confirmed that Apple was a victim. In all, 17 people confirmed the manipulation of Supermicro’s hardware and other elements of the attacks. The sources were granted anonymity because of the sensitive, and in some cases classified, nature of the information.

One government official says China’s goal was long-term access to high-value corporate secrets and sensitive government networks. No consumer data is known to have been stolen.

The ramifications of the attack continue to play out. The Trump administration has made computer and networking hardware, including motherboards, a focus of its latest round of trade sanctions against China, and White House officials have made it clear they think companies will begin shifting their supply chains to other countries as a result. Such a shift might assuage officials who have been warning for years about the security of the supply chain—even though they’ve never disclosed a major reason for their concerns.

How the Hack Worked, According to U.S. Officials

Illustrator: Scott Gelber스콧 겔버

Back in 2006, three engineers in Oregon had a clever idea. Demand for mobile video was about to explode, and they predicted that broadcasters would be desperate to transform programs designed to fit TV screens into the various formats needed for viewing on smartphones, laptops, and other devices. To meet the anticipated demand, the engineers started Elemental Technologies, assembling what one former adviser to the company calls a genius team to write code that would adapt the superfast graphics chips being produced for high-end video-gaming machines. The resulting software dramatically reduced the time it took to process large video files. Elemental then loaded the software onto custom-built servers emblazoned with its leprechaun-green logos.

Elemental servers sold for as much as $100,000 each, at profit margins of as high as 70 percent, according to a former adviser to the company. Two of Elemental’s biggest early clients were the Mormon church, which used the technology to beam sermons to congregations around the world, and the adult film industry, which did not.

Elemental also started working with American spy agencies. In 2009 the company announced a development partnership with In-Q-Tel Inc., the CIA’s investment arm, a deal that paved the way for Elemental servers to be used in national security missions across the U.S. government. Public documents, including the company’s own promotional materials, show that the servers have been used inside Department of Defense data centers to process drone and surveillance-camera footage, on Navy warships to transmit feeds of airborne missions, and inside government buildings to enable secure videoconferencing. NASA, both houses of Congress, and the Department of Homeland Security have also been customers. This portfolio made Elemental a target for foreign adversaries.

Supermicro had been an obvious choice to build Elemental’s servers. Headquartered north of San Jose’s airport, up a smoggy stretch of Interstate 880, the company was founded by Charles Liang, a Taiwanese engineer who attended graduate school in Texas and then moved west to start Supermicro with his wife in 1993. Silicon Valley was then embracing outsourcing, forging a pathway from Taiwanese, and later Chinese, factories to American consumers, and Liang added a comforting advantage: Supermicro’s motherboards would be engineered mostly in San Jose, close to the company’s biggest clients, even if the products were manufactured overseas.

Today, Supermicro sells more server motherboards than almost anyone else. It also dominates the $1 billion market for boards used in special-purpose computers, from MRI machines to weapons systems. Its motherboards can be found in made-to-order server setups at banks, hedge funds, cloud computing providers, and web-hosting services, among other places. Supermicro has assembly facilities in California, the Netherlands, and Taiwan, but its motherboards—its core product—are nearly all manufactured by contractors in China.

The company’s pitch to customers hinges on unmatched customization, made possible by hundreds of full-time engineers and a catalog encompassing more than 600 designs. The majority of its workforce in San Jose is Taiwanese or Chinese, and Mandarin is the preferred language, with hanzi filling the whiteboards, according to six former employees. Chinese pastries are delivered every week, and many routine calls are done twice, once for English-only workers and again in Mandarin. The latter are more productive, according to people who’ve been on both. These overseas ties, especially the widespread use of Mandarin, would have made it easier for China to gain an understanding of Supermicro’s operations and potentially to infiltrate the company. (A U.S. official says the government’s probe is still examining whether spies were planted inside Supermicro or other American companies to aid the attack.)

With more than 900 customers in 100 countries by 2015, Supermicro offered inroads to a bountiful collection of sensitive targets. “Think of Supermicro as the Microsoft of the hardware world,” says a former U.S. intelligence official who’s studied Supermicro and its business model. “Attacking Supermicro motherboards is like attacking Windows. It’s like attacking the whole world.”

The security of the global technology supply chain had been compromised, even if consumers and most companies didn’t know it yet

Well before evidence of the attack surfaced inside the networks of U.S. companies, American intelligence sources were reporting that China’s spies had plans to introduce malicious microchips into the supply chain. The sources weren’t specific, according to a person familiar with the information they provided, and millions of motherboards are shipped into the U.S. annually. But in the first half of 2014, a different person briefed on high-level discussions says, intelligence officials went to the White House with something more concrete: China’s military was preparing to insert the chips into Supermicro motherboards bound for U.S. companies.

The specificity of the information was remarkable, but so were the challenges it posed. Issuing a broad warning to Supermicro’s customers could have crippled the company, a major American hardware maker, and it wasn’t clear from the intelligence whom the operation was targeting or what its ultimate aims were. Plus, without confirmation that anyone had been attacked, the FBI was limited in how it could respond. The White House requested periodic updates as information came in, the person familiar with the discussions says.

Apple made its discovery of suspicious chips inside Supermicro servers around May 2015, after detecting odd network activity and firmware problems, according to a person familiar with the timeline. Two of the senior Apple insiders say the company reported the incident to the FBI but kept details about what it had detected tightly held, even internally. Government investigators were still chasing clues on their own when Amazon made its discovery and gave them access to sabotaged hardware, according to one U.S. official. This created an invaluable opportunity for intelligence agencies and the FBI—by then running a full investigation led by its cyber- and counterintelligence teams—to see what the chips looked like and how they worked.

The chips on Elemental servers were designed to be as inconspicuous as possible, according to one person who saw a detailed report prepared for Amazon by its third-party security contractor, as well as a second person who saw digital photos and X-ray images of the chips incorporated into a later report prepared by Amazon’s security team. Gray or off-white in color, they looked more like signal conditioning couplers, another common motherboard component, than microchips, and so they were unlikely to be detectable without specialized equipment. Depending on the board model, the chips varied slightly in size, suggesting that the attackers had supplied different factories with different batches.

Officials familiar with the investigation say the primary role of implants such as these is to open doors that other attackers can go through. “Hardware attacks are about access,” as one former senior official puts it. In simplified terms, the implants on Supermicro hardware manipulated the core operating instructions that tell the server what to do as data move across a motherboard, two people familiar with the chips’ operation say. This happened at a crucial moment, as small bits of the operating system were being stored in the board’s temporary memory en route to the server’s central processor, the CPU. The implant was placed on the board in a way that allowed it to effectively edit this information queue, injecting its own code or altering the order of the instructions the CPU was meant to follow. Deviously small changes could create disastrous effects.

Since the implants were small, the amount of code they contained was small as well. But they were capable of doing two very important things: telling the device to communicate with one of several anonymous computers elsewhere on the internet that were loaded with more complex code; and preparing the device’s operating system to accept this new code. The illicit chips could do all this because they were connected to the baseboard management controller, a kind of superchip that administrators use to remotely log in to problematic servers, giving them access to the most sensitive code even on machines that have crashed or are turned off.

This system could let the attackers alter how the device functioned, line by line, however they wanted, leaving no one the wiser. To understand the power that would give them, take this hypothetical example: Somewhere in the Linux operating system, which runs in many servers, is code that authorizes a user by verifying a typed password against a stored encrypted one. An implanted chip can alter part of that code so the server won’t check for a password—and presto! A secure machine is open to any and all users. A chip can also steal encryption keys for secure communications, block security updates that would neutralize the attack, and open up new pathways to the internet. Should some anomaly be noticed, it would likely be cast as an unexplained oddity. “The hardware opens whatever door it wants,” says Joe FitzPatrick, founder of Hardware Security Resources LLC, a company that trains cybersecurity professionals in hardware hacking techniques.

U.S. officials had caught China experimenting with hardware tampering before, but they’d never seen anything of this scale and ambition. The security of the global technology supply chain had been compromised, even if consumers and most companies didn’t know it yet. What remained for investigators to learn was how the attackers had so thoroughly infiltrated Supermicro’s production process—and how many doors they’d opened into American targets.

Unlike software-based hacks, hardware manipulation creates a real-world trail. Components leave a wake of shipping manifests and invoices. Boards have serial numbers that trace to specific factories. To track the corrupted chips to their source, U.S. intelligence agencies began following Supermicro’s serpentine supply chain in reverse, a person briefed on evidence gathered during the probe says.

As recently as 2016, according to DigiTimes, a news site specializing in supply chain research, Supermicro had three primary manufacturers constructing its motherboards, two headquartered in Taiwan and one in Shanghai. When such suppliers are choked with big orders, they sometimes parcel out work to subcontractors. In order to get further down the trail, U.S. spy agencies drew on the prodigious tools at their disposal. They sifted through communications intercepts, tapped informants in Taiwan and China, even tracked key individuals through their phones, according to the person briefed on evidence gathered during the probe. Eventually, that person says, they traced the malicious chips to four subcontracting factories that had been building Supermicro motherboards for at least two years.

As the agents monitored interactions among Chinese officials, motherboard manufacturers, and middlemen, they glimpsed how the seeding process worked. In some cases, plant managers were approached by people who claimed to represent Supermicro or who held positions suggesting a connection to the government. The middlemen would request changes to the motherboards’ original designs, initially offering bribes in conjunction with their unusual requests. If that didn’t work, they threatened factory managers with inspections that could shut down their plants. Once arrangements were in place, the middlemen would organize delivery of the chips to the factories.

The investigators concluded that this intricate scheme was the work of a People’s Liberation Army unit specializing in hardware attacks, according to two people briefed on its activities. The existence of this group has never been revealed before, but one official says, “We’ve been tracking these guys for longer than we’d like to admit.” The unit is believed to focus on high-priority targets, including advanced commercial technology and the computers of rival militaries. In past attacks, it targeted the designs for high-performance computer chips and computing systems of large U.S. internet providers.

Provided details of Businessweek’s reporting, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent a statement that said “China is a resolute defender of cybersecurity.” The ministry added that in 2011, China proposed international guarantees on hardware security along with other members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a regional security body. The statement concluded, “We hope parties make less gratuitous accusations and suspicions but conduct more constructive talk and collaboration so that we can work together in building a peaceful, safe, open, cooperative and orderly cyberspace.”

The Supermicro attack was on another order entirely from earlier episodes attributed to the PLA. It threatened to have reached a dizzying array of end users, with some vital ones in the mix. Apple, for its part, has used Supermicro hardware in its data centers sporadically for years, but the relationship intensified after 2013, when Apple acquired a startup called Topsy Labs, which created superfast technology for indexing and searching vast troves of internet content. By 2014, the startup was put to work building small data centers in or near major global cities. This project, known internally as Ledbelly, was designed to make the search function for Apple’s voice assistant, Siri, faster, according to the three senior Apple insiders.

Documents seen by Businessweek show that in 2014, Apple planned to order more than 6,000 Supermicro servers for installation in 17 locations, including Amsterdam, Chicago, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, New York, San Jose, Singapore, and Tokyo, plus 4,000 servers for its existing North Carolina and Oregon data centers. Those orders were supposed to double, to 20,000, by 2015. Ledbelly made Apple an important Supermicro customer at the exact same time the PLA was found to be manipulating the vendor’s hardware.

Project delays and early performance problems meant that around 7,000 Supermicro servers were humming in Apple’s network by the time the company’s security team found the added chips. Because Apple didn’t, according to a U.S. official, provide government investigators with access to its facilities or the tampered hardware, the extent of the attack there remained outside their view.

American investigators eventually figured out who else had been hit. Since the implanted chips were designed to ping anonymous computers on the internet for further instructions, operatives could hack those computers to identify others who’d been affected. Although the investigators couldn’t be sure they’d found every victim, a person familiar with the U.S. probe says they ultimately concluded that the number was almost 30 companies.

That left the question of whom to notify and how. U.S. officials had been warning for years that hardware made by two Chinese telecommunications giants, Huawei Corp. and ZTE Corp., was subject to Chinese government manipulation. (Both Huawei and ZTE have said no such tampering has occurred.) But a similar public alert regarding a U.S. company was out of the question. Instead, officials reached out to a small number of important Supermicro customers. One executive of a large web-hosting company says the message he took away from the exchange was clear: Supermicro’s hardware couldn’t be trusted. “That’s been the nudge to everyone—get that crap out,” the person says.

Amazon, for its part, began acquisition talks with an Elemental competitor, but according to one person familiar with Amazon’s deliberations, it reversed course in the summer of 2015 after learning that Elemental’s board was nearing a deal with another buyer. Amazon announced its acquisition of Elemental in September 2015, in a transaction whose value one person familiar with the deal places at $350 million. Multiple sources say that Amazon intended to move Elemental’s software to AWS’s cloud, whose chips, motherboards, and servers are typically designed in-house and built by factories that Amazon contracts from directly.

A notable exception was AWS’s data centers inside China, which were filled with Supermicro-built servers, according to two people with knowledge of AWS’s operations there. Mindful of the Elemental findings, Amazon’s security team conducted its own investigation into AWS’s Beijing facilities and found altered motherboards there as well, including more sophisticated designs than they’d previously encountered. In one case, the malicious chips were thin enough that they’d been embedded between the layers of fiberglass onto which the other components were attached, according to one person who saw pictures of the chips. That generation of chips was smaller than a sharpened pencil tip, the person says. (Amazon denies that AWS knew of servers found in China containing malicious chips.)

China has long been known to monitor banks, manufacturers, and ordinary citizens on its own soil, and the main customers of AWS’s China cloud were domestic companies or foreign entities with operations there. Still, the fact that the country appeared to be conducting those operations inside Amazon’s cloud presented the company with a Gordian knot. Its security team determined that it would be difficult to quietly remove the equipment and that, even if they could devise a way, doing so would alert the attackers that the chips had been found, according to a person familiar with the company’s probe. Instead, the team developed a method of monitoring the chips. In the ensuing months, they detected brief check-in communications between the attackers and the sabotaged servers but didn’t see any attempts to remove data. That likely meant either that the attackers were saving the chips for a later operation or that they’d infiltrated other parts of the network before the monitoring began. Neither possibility was reassuring.

When in 2016 the Chinese government was about to pass a new cybersecurity law—seen by many outside the country as a pretext to give authorities wider access to sensitive data—Amazon decided to act, the person familiar with the company’s probe says. In August it transferred operational control of its Beijing data center to its local partner, Beijing Sinnet, a move the companies said was needed to comply with the incoming law. The following November, Amazon sold the entire infrastructure to Beijing Sinnet for about $300 million. The person familiar with Amazon’s probe casts the sale as a choice to “hack off the diseased limb.”

As for Apple, one of the three senior insiders says that in the summer of 2015, a few weeks after it identified the malicious chips, the company started removing all Supermicro servers from its data centers, a process Apple referred to internally as “going to zero.” Every Supermicro server, all 7,000 or so, was replaced in a matter of weeks, the senior insider says. (Apple denies that any servers were removed.) In 2016, Apple informed Supermicro that it was severing their relationship entirely—a decision a spokesman for Apple ascribed in response to Businessweek’s questions to an unrelated and relatively minor security incident.

That August, Supermicro’s CEO, Liang, revealed that the company had lost two major customers. Although he didn’t name them, one was later identified in news reports as Apple. He blamed competition, but his explanation was vague. “When customers asked for lower price, our people did not respond quickly enough,” he said on a conference call with analysts. Hayes, the Supermicro spokesman, says the company has never been notified of the existence of malicious chips on its motherboards by either customers or U.S. law enforcement.

Concurrent with the illicit chips’ discovery in 2015 and the unfolding investigation, Supermicro has been plagued by an accounting problem, which the company characterizes as an issue related to the timing of certain revenue recognition. After missing two deadlines to file quarterly and annual reports required by regulators, Supermicro was delisted from the Nasdaq on Aug. 23 of this year. It marked an extraordinary stumble for a company whose annual revenue had risen sharply in the previous four years, from a reported $1.5 billion in 2014 to a projected $3.2 billion this year.

One Friday in late September 2015, President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping appeared together at the White House for an hourlong press conference headlined by a landmark deal on cybersecurity. After months of negotiations, the U.S. had extracted from China a grand promise: It would no longer support the theft by hackers of U.S. intellectual property to benefit Chinese companies. Left out of those pronouncements, according to a person familiar with discussions among senior officials across the U.S. government, was the White House’s deep concern that China was willing to offer this concession because it was already developing far more advanced and surreptitious forms of hacking founded on its near monopoly of the technology supply chain.

In the weeks after the agreement was announced, the U.S. government quietly raised the alarm with several dozen tech executives and investors at a small, invite-only meeting in McLean, Va., organized by the Pentagon. According to someone who was present, Defense Department officials briefed the technologists on a recent attack and asked them to think about creating commercial products that could detect hardware implants. Attendees weren’t told the name of the hardware maker involved, but it was clear to at least some in the room that it was Supermicro, the person says.

The problem under discussion wasn’t just technological. It spoke to decisions made decades ago to send advanced production work to Southeast Asia. In the intervening years, low-cost Chinese manufacturing had come to underpin the business models of many of America’s largest technology companies. Early on, Apple, for instance, made many of its most sophisticated electronics domestically. Then in 1992, it closed a state-of-the-art plant for motherboard and computer assembly in Fremont, Calif., and sent much of that work overseas.

Over the decades, the security of the supply chain became an article of faith despite repeated warnings by Western officials. A belief formed that China was unlikely to jeopardize its position as workshop to the world by letting its spies meddle in its factories. That left the decision about where to build commercial systems resting largely on where capacity was greatest and cheapest. “You end up with a classic Satan’s bargain,” one former U.S. official says. “You can have less supply than you want and guarantee it’s secure, or you can have the supply you need, but there will be risk. Every organization has accepted the second proposition.”

In the three years since the briefing in McLean, no commercially viable way to detect attacks like the one on Supermicro’s motherboards has emerged—or has looked likely to emerge. Few companies have the resources of Apple and Amazon, and it took some luck even for them to spot the problem. “This stuff is at the cutting edge of the cutting edge, and there is no easy technological solution,” one of the people present in McLean says. “You have to invest in things that the world wants. You cannot invest in things that the world is not ready to accept yet.”

Bloomberg LP has been a Supermicro customer. According to a Bloomberg LP spokesperson, the company has found no evidence to suggest that it has been affected by the hardware issues raised in the article.

빅 해킹: 중국이 작은 칩을 사용하여 미국 기업에 침투한 방법

정부 및 기업 소식통과의 광범위한 인터뷰에 따르면 중국 스파이의 공격은 미국의 기술 공급망을 손상시켜 아마존과 애플을 포함한 거의 30개 미국 기업에 영향을 미쳤습니다.

2015년에 Amazon.com Inc. 는 현재 Amazon Prime Video로 알려진 스트리밍 비디오 서비스의 주요 확장을 지원하기 위해 잠재적인 인수인 Elemental Technologies 라는 신생 기업을 조용히 평가하기 시작했습니다 . 오리건주 포틀랜드에 기반을 둔 Elemental은 대용량 비디오 파일을 압축하고 다양한 장치에 맞게 포맷하기 위한 소프트웨어를 만들었습니다. 그 기술은 올림픽 게임을 온라인으로 스트리밍하고, 국제 우주 정거장과 통신하고, 무인 항공기 영상을 중앙 정보국에 보내는 데 도움이 되었습니다. 엘리멘탈의 국가 보안 계약은 인수 제안의 주된 이유는 아니었지만, 아마존 웹 서비스(AWS)가 CIA를 위해 구축하고 있던 고도로 안전한 클라우드와 같은 아마존의 정부 사업과 잘 맞았습니다.

프로세스에 정통한 한 관계자에 따르면 실사를 돕기 위해 향후 인수를 감독하고 있던 AWS가 Elemental의 보안을 조사하기 위해 제3자 회사를 고용했습니다. 첫 번째 단계에서는 문제가 되는 문제를 발견하여 AWS가 Elemental의 주요 제품인 비디오 압축을 처리하기 위해 네트워크에 설치한 값비싼 서버를 자세히 살펴보도록 했습니다.

이 서버는 Super Micro Computer Inc. 에서 Elemental용으로 조립했습니다 ., 서버 마더보드, 크고 작은 데이터 센터의 뉴런 역할을 하는 유리 섬유 장착 칩 및 커패시터 클러스터의 세계 최대 공급업체이기도 한 산호세에 기반을 둔 회사(일반적으로 Supermicro로 알려짐)입니다. 2015년 늦봄에 Elemental의 직원은 타사 보안 회사가 테스트할 수 있도록 여러 대의 서버를 포장하여 캐나다 온타리오로 보냈습니다.

서버의 마더보드에 중첩된 테스터는 보드의 원래 디자인의 일부가 아닌 쌀알보다 크지 않은 작은 마이크로칩을 발견했습니다. 아마존은 이 발견을 미국 당국에 보고했고, 정보 커뮤니티는 전율을 느꼈다. Elemental의 서버는 국방부 데이터 센터, CIA의 무인 항공기 작전 및 해군 전함의 온보드 네트워크에서 찾을 수 있습니다. 그리고 Elemental은 수백 명의 Supermicro 고객 중 하나에 불과했습니다.

3년 이상이 지난 후에도 여전히 공개된 뒤이은 극비 조사에서 조사관은 칩을 통해 공격자가 변경된 기계가 포함된 모든 네트워크에 은밀한 출입구를 만들 수 있다고 결정했습니다. 이 문제에 정통한 여러 사람들은 조사관들이 중국의 제조 하청업체가 운영하는 공장에 칩이 삽입된 것을 발견했다고 말했습니다.

이 공격은 전 세계가 익숙해진 소프트웨어 기반 사건보다 더 심각한 것이었습니다. 하드웨어 해킹은 제거하기가 더 어렵고 잠재적으로 더 파괴적이며, 스파이 기관이 수백만 달러와 수년을 투자할 의향이 있는 일종의 장기 은밀한 액세스를 약속합니다.

"국가 수준의 하드웨어 임플란트 표면을 잘 만든 것은 무지개를 뛰어넘는 유니콘을 목격하는 것과 같습니다."

스파이가 컴퓨터 장비의 내장을 변경하는 방법에는 두 가지가 있습니다. 차단이라고 하는 하나는 제조업체에서 고객으로 이동하는 장치를 조작하는 것으로 구성됩니다. 전직 국가안보국 계약자 에드워드 스노든(Edward Snowden)이 유출한 문서에 따르면, 이 접근 방식은 미국 스파이 기관에서 선호합니다. 다른 방법은 처음부터 변경 사항을 파종하는 것입니다.

특히 한 국가는 이러한 종류의 공격을 실행하는 데 유리합니다. 일부 추정에 따르면 세계 휴대폰의 75%와 PC의 90%를 차지하는 중국입니다. 그러나 실제로 시딩 공격을 수행하려면 제품 설계에 대한 깊은 이해를 개발하고 공장에서 구성 요소를 조작하며 조작된 장치가 글로벌 물류 체인을 통해 원하는 위치로 전달되도록 하는 것을 의미합니다. 이는 막대기를 던지는 것과 유사한 위업입니다. 상하이에서 양쯔강 상류로 흐르고 시애틀에서 해안으로 흘러가도록 합니다. 하드웨어 해커이자 Grand Idea Studio Inc 의 설립자인 Joe Grand는 "국가 수준의 하드웨어 임플란트 표면을 잘 만든 것은 유니콘이 무지개를 뛰어넘는 것을 목격하는 것과 같습니다."라고 말합니다 . "하드웨어는 레이더에서 너무 멀리 떨어져 있어 거의 흑마술처럼 취급됩니다."

그러나 그것은 미국 수사관들이 발견한 것입니다. 두 관리는 칩이 제조 과정에서 인민해방군 부대의 요원에 의해 삽입되었다고 말했습니다. Supermicro에서 중국의 스파이는 미국 관리들이 현재 미국 기업에 대해 수행된 것으로 알려진 가장 심각한 공급망 공격으로 설명하는 완벽한 통로를 찾은 것으로 보입니다.

한 관계자는 조사관들이 주요 은행, 정부 계약자, 세계에서 가장 가치 있는 회사인 Apple Inc.를 포함하여 거의 30개 회사에 결국 영향을 미쳤음을 발견했다고 밝혔습니다 . Apple은 Supermicro의 중요한 고객이었고 두 대의 서버로 30,000대 이상의 서버를 주문할 계획이었습니다. 데이터 센터의 새로운 글로벌 네트워크를 위한 몇 년. Apple의 3명의 고위 내부자는 2015년 여름에 Supermicro 마더보드에서도 악성 칩을 발견했다고 말했습니다. Apple은 다음 해에 관련 없는 이유로 Supermicro와 관계를 끊었습니다.

아마존은 "AWS가 Elemental 인수 시 공급망 손상, 악성 칩 문제 또는 하드웨어 수정에 대해 알았다는 것은 사실이 아니다"라고 적었다. Apple은 "이에 대해 우리는 매우 분명합니다. Apple은 악성 칩, '하드웨어 조작' 또는 서버에 의도적으로 심어진 취약점을 발견한 적이 없습니다."라고 썼습니다. Supermicro의 대변인 Perry Hayes는 "우리는 그러한 조사에 대해 알지 못합니다."라고 말했습니다. 중국 정부는 슈퍼마이크로 서버 조작에 대한 질문에 직접적으로 답하지 않고 부분적으로 "사이버 공간의 공급망 안전은 공통 관심사이며 중국도 피해자"라는 성명을 발표했다. CIA와 NSA를 대표하는 FBI와 국가정보국장실은 논평을 거부했다.

이 회사의 부인은 오바마 행정부에서 시작되어 트럼프 행정부에서 계속된 6명의 전·현직 국가 안보 관리가 반박했으며, 이들은 칩 발견과 정부의 조사에 대해 자세히 설명했습니다. 그 관리 중 한 명과 AWS 내부의 두 사람은 Elemental과 Amazon에서 공격이 어떻게 진행되었는지에 대한 광범위한 정보를 제공했습니다. 이 관계자와 내부자 중 한 명은 아마존이 정부 조사에 협조했다고 설명하기도 했다. 애플 내부 관계자 3명 외에도 미국 관리 6명 중 4명은 애플이 피해자임을 확인했다. 모두 17명이 슈퍼마이크로의 하드웨어 조작 및 기타 공격 요소를 확인했다. 정보의 민감하고 어떤 경우에는 기밀로 분류되기 때문에 출처는 익명이 허용되었습니다.

한 정부 관리는 중국의 목표는 가치가 높은 기업 기밀과 민감한 정부 네트워크에 장기간 접근하는 것이라고 말했습니다. 어떠한 소비자 데이터도 도난당한 것으로 알려져 있지 않습니다.

공격의 여파는 계속됩니다. 트럼프 행정부는 마더보드를 포함한 컴퓨터 및 네트워킹 하드웨어를 최근 중국에 대한 무역 제재의 초점으로 삼았고, 백악관 관리들은 결과적으로 기업들이 공급망을 다른 국가로 이전하기 시작할 것이라고 생각한다는 점을 분명히 했습니다. 이러한 변화는 공급망의 보안에 대해 수년간 경고해 온 관리들을 안심시킬 수 있습니다. 비록 우려의 주요 이유를 공개한 적이 없음에도 불구하고 말입니다.

3년 이상이 지난 후에도 여전히 공개된 뒤이은 극비 조사에서 조사관은 칩을 통해 공격자가 변경된 기계가 포함된 모든 네트워크에 은밀한 출입구를 만들 수 있다고 결정했습니다. 이 문제에 정통한 여러 사람들은 조사관들이 중국의 제조 하청업체가 운영하는 공장에 칩이 삽입된 것을 발견했다고 말했습니다.

이 공격은 전 세계가 익숙해진 소프트웨어 기반 사건보다 더 심각한 것이었습니다. 하드웨어 해킹은 제거하기가 더 어렵고 잠재적으로 더 파괴적이며, 스파이 기관이 수백만 달러와 수년을 투자할 의향이 있는 일종의 장기 은밀한 액세스를 약속합니다.

"국가 수준의 하드웨어 임플란트 표면을 잘 만든 것은 무지개를 뛰어넘는 유니콘을 목격하는 것과 같습니다."

스파이가 컴퓨터 장비의 내장을 변경하는 방법에는 두 가지가 있습니다. 차단이라고 하는 하나는 제조업체에서 고객으로 이동하는 장치를 조작하는 것으로 구성됩니다. 전직 국가안보국 계약자 에드워드 스노든(Edward Snowden)이 유출한 문서에 따르면, 이 접근 방식은 미국 스파이 기관에서 선호합니다. 다른 방법은 처음부터 변경 사항을 파종하는 것입니다.

특히 한 국가는 이러한 종류의 공격을 실행하는 데 유리합니다. 일부 추정에 따르면 세계 휴대폰의 75%와 PC의 90%를 차지하는 중국입니다. 그러나 실제로 시딩 공격을 수행하려면 제품 설계에 대한 깊은 이해를 개발하고 공장에서 구성 요소를 조작하며 조작된 장치가 글로벌 물류 체인을 통해 원하는 위치로 전달되도록 하는 것을 의미합니다. 이는 막대기를 던지는 것과 유사한 위업입니다. 상하이에서 양쯔강 상류로 흐르고 시애틀에서 해안으로 흘러가도록 합니다. 하드웨어 해커이자 Grand Idea Studio Inc 의 설립자인 Joe Grand는 "국가 수준의 하드웨어 임플란트 표면을 잘 만든 것은 유니콘이 무지개를 뛰어넘는 것을 목격하는 것과 같습니다."라고 말합니다 . "하드웨어는 레이더에서 너무 멀리 떨어져 있어 거의 흑마술처럼 취급됩니다."

그러나 그것은 미국 수사관들이 발견한 것입니다. 두 관리는 칩이 제조 과정에서 인민해방군 부대의 요원에 의해 삽입되었다고 말했습니다. Supermicro에서 중국의 스파이는 미국 관리들이 현재 미국 기업에 대해 수행된 것으로 알려진 가장 심각한 공급망 공격으로 설명하는 완벽한 통로를 찾은 것으로 보입니다.

한 관계자는 조사관들이 주요 은행, 정부 계약자, 세계에서 가장 가치 있는 회사인 Apple Inc.를 포함하여 거의 30개 회사에 결국 영향을 미쳤음을 발견했다고 밝혔습니다 . Apple은 Supermicro의 중요한 고객이었고 두 대의 서버로 30,000대 이상의 서버를 주문할 계획이었습니다. 데이터 센터의 새로운 글로벌 네트워크를 위한 몇 년. Apple의 3명의 고위 내부자는 2015년 여름에 Supermicro 마더보드에서도 악성 칩을 발견했다고 말했습니다. Apple은 다음 해에 관련 없는 이유로 Supermicro와 관계를 끊었습니다.

아마존은 "AWS가 Elemental 인수 시 공급망 손상, 악성 칩 문제 또는 하드웨어 수정에 대해 알았다는 것은 사실이 아니다"라고 적었다. Apple은 "이에 대해 우리는 매우 분명합니다. Apple은 악성 칩, '하드웨어 조작' 또는 서버에 의도적으로 심어진 취약점을 발견한 적이 없습니다."라고 썼습니다. Supermicro의 대변인 Perry Hayes는 "우리는 그러한 조사에 대해 알지 못합니다."라고 말했습니다. 중국 정부는 슈퍼마이크로 서버 조작에 대한 질문에 직접적으로 답하지 않고 부분적으로 "사이버 공간의 공급망 안전은 공통 관심사이며 중국도 피해자"라는 성명을 발표했다. CIA와 NSA를 대표하는 FBI와 국가정보국장실은 논평을 거부했다.

이 회사의 부인은 오바마 행정부에서 시작되어 트럼프 행정부에서 계속된 6명의 전·현직 국가 안보 관리가 반박했으며, 이들은 칩 발견과 정부의 조사에 대해 자세히 설명했습니다. 그 관리 중 한 명과 AWS 내부의 두 사람은 Elemental과 Amazon에서 공격이 어떻게 진행되었는지에 대한 광범위한 정보를 제공했습니다. 이 관계자와 내부자 중 한 명은 아마존이 정부 조사에 협조했다고 설명하기도 했다. 애플 내부 관계자 3명 외에도 미국 관리 6명 중 4명은 애플이 피해자임을 확인했다. 모두 17명이 슈퍼마이크로의 하드웨어 조작 및 기타 공격 요소를 확인했다. 정보의 민감하고 어떤 경우에는 기밀로 분류되기 때문에 출처는 익명이 허용되었습니다.

한 정부 관리는 중국의 목표는 가치가 높은 기업 기밀과 민감한 정부 네트워크에 장기간 접근하는 것이라고 말했습니다. 어떠한 소비자 데이터도 도난당한 것으로 알려져 있지 않습니다.

공격의 여파는 계속됩니다. 트럼프 행정부는 마더보드를 포함한 컴퓨터 및 네트워킹 하드웨어를 최근 중국에 대한 무역 제재의 초점으로 삼았고, 백악관 관리들은 결과적으로 기업들이 공급망을 다른 국가로 이전하기 시작할 것이라고 생각한다는 점을 분명히 했습니다. 이러한 변화는 공급망의 보안에 대해 수년간 경고해 온 관리들을 안심시킬 수 있습니다. 비록 우려의 주요 이유를 공개한 적이 없음에도 불구하고 말입니다.

미국 관리에 따르면 해킹이 작동한 방식

① 중국군 부대는 100cm 이하의 초소형 마이크로칩을 설계·제작했다. 뾰족한 연필 끝. 일부 칩은 신호 조절 커플러처럼 보이도록 제작되었으며 메모리, 네트워킹 기능 및 공격에 대한 충분한 처리 능력을 통합했습니다.

② 세계 최대 서버 마더보드 판매업체인 슈퍼마이크로를 공급한 중국 공장에 마이크로칩이 삽입됐다.

③ 훼손된 마더보드는 Supermicro에서 조립한 서버에 내장되었습니다.

④ 파괴된 서버는 수십 개의 회사가 운영하는 데이터 센터 내부로 침투했습니다.

⑤ 서버가 설치되고 스위치가 켜질 때 마이크로칩은 운영 체제의 코어를 변경하여 수정 사항을 수용할 수 있도록 했습니다. 이 칩은 추가 지침과 코드를 찾기 위해 공격자가 제어하는 컴퓨터와 접촉할 수도 있습니다.

2006년에 오리건의 세 엔지니어는 기발한 아이디어를 냈습니다. 모바일 비디오에 대한 수요가 폭발적으로 증가할 것이며 방송사는 TV 화면에 맞게 설계된 프로그램을 스마트폰, 랩톱 및 기타 장치에서 시청하는 데 필요한 다양한 형식으로 변환하는 데 필사적일 것이라고 예측했습니다. 예상되는 수요를 충족시키기 위해 엔지니어들은 Elemental Technologies를 시작했으며, 회사의 전 고문 중 한 명이 천재 팀이라고 부르는 고급 비디오 게임기용으로 생산되는 초고속 그래픽 칩을 적용할 코드를 작성하는 팀을 구성했습니다. 결과 소프트웨어는 대용량 비디오 파일을 처리하는 데 걸리는 시간을 크게 줄였습니다. 그런 다음 Elemental은 레프리콘 로고가 새겨진 맞춤형 서버에 소프트웨어를 로드했습니다.

회사의 전 고문에 따르면 Elemental 서버는 최대 70%의 이윤으로 각 $100,000에 판매되었습니다. Elemental의 가장 큰 초기 고객 중 두 곳은 기술을 사용하여 전 세계 교회에 설교를 전파하는 모르몬 교회와 그렇지 않은 성인 영화 산업이었습니다.

Elemental은 또한 미국 첩보 기관과 협력하기 시작했습니다. 2009년에 회사는 CIA의 투자 부서인 In-Q-Tel Inc. 와의 개발 파트너십을 발표했으며 , 이 거래를 통해 Elemental 서버가 미국 정부의 국가 안보 임무에 사용될 수 있는 기반을 마련했습니다. 회사의 자체 홍보 자료를 포함한 공개 문서에 따르면 서버는 국방부 데이터 센터 내부에서 드론 및 감시 카메라 영상을 처리하고 해군 군함에서 공수 임무 피드를 전송하고 정부 건물 내부에서 안전한 화상 회의를 지원하는 데 사용되었음을 보여줍니다. . NASA, 양원, 국토안보부도 고객이었습니다. 이 포트폴리오는 Elemental을 외국 적의 표적으로 만들었습니다.

Supermicro는 Elemental의 서버를 구축하기 위한 확실한 선택이었습니다. 산호세 공항 북쪽에 본사가 있으며 880번 고속도로의 안개가 자욱한 곳에 위치한 이 회사는 텍사스에서 대학원을 다녔다가 1993년 아내와 함께 서부로 이동하여 Supermicro를 시작하기 위해 서부로 이사한 대만 엔지니어 Charles Liang에 의해 설립되었습니다. 아웃소싱을 통해 대만 및 이후 중국 공장에서 미국 소비자로 가는 경로를 구축했으며 Liang은 위안이 되는 이점을 추가했습니다. Supermicro의 마더보드는 제품이 해외에서 제조되더라도 회사의 가장 큰 고객과 가까운 산호세에서 대부분 설계될 것입니다.

오늘날 Supermicro는 거의 모든 사람보다 더 많은 서버 마더보드를 판매하고 있습니다. 또한 MRI 기계에서 무기 시스템에 이르기까지 특수 목적 컴퓨터에 사용되는 보드의 10억 달러 시장을 장악하고 있습니다. 마더보드는 은행, 헤지 펀드, 클라우드 컴퓨팅 제공업체, 웹 호스팅 서비스 등의 주문형 서버 설정에서 찾을 수 있습니다. Supermicro는 캘리포니아, 네덜란드, 대만에 조립 시설을 가지고 있지만 핵심 제품인 마더보드는 거의 모두 중국의 계약업체에서 제조합니다.

고객에 대한 회사의 프레젠테이션은 수백 명의 정규직 엔지니어와 600개 이상의 디자인을 포함하는 카탈로그에 의해 가능해진 비할 데 없는 맞춤화에 달려 있습니다. 산호세 인력의 대부분은 대만, 중국어, 그리고 만다린으로, 선호하는 언어 한자6명의 전직 직원에 따르면 화이트보드를 채우고 있습니다. 매주 중국식 패스트리가 배달되며 많은 일상적인 전화가 두 번 이루어집니다. 한 번은 영어만 하는 직원을 위한 것이고 또 한 번은 만다린어로 하는 것입니다. 둘 다 사용해 본 사람들에 따르면 후자가 더 생산적입니다. 이러한 해외 관계, 특히 만다린어의 광범위한 사용은 중국이 Supermicro의 운영을 이해하고 잠재적으로 회사에 침투하는 것을 더 쉽게 만들었습니다. (미국 관리는 정부의 조사가 공격을 돕기 위해 Supermicro 또는 다른 미국 회사에 스파이를 심어 놓았는지 여부를 여전히 조사하고 있다고 말했습니다.)

2015년까지 100개국에서 900명 이상의 고객과 함께 Supermicro는 민감한 표적의 풍부한 컬렉션에 진출할 수 있는 기회를 제공했습니다. Supermicro와 그 비즈니스 모델을 연구한 전직 미국 정보 당국자는 "Supermicro를 하드웨어 세계의 Microsoft로 생각하십시오."라고 말했습니다. “Supermicro 마더보드를 공격하는 것은 Windows를 공격하는 것과 같습니다. 전 세계를 공격하는 것과 같습니다.”

소비자와 대부분의 기업이 아직 알지 못하더라도 글로벌 기술 공급망의 보안이 손상되었습니다.

공격의 증거가 미국 기업의 네트워크 내부에 나타나기 훨씬 전에 미국 정보원은 중국의 스파이가 공급망에 악성 마이크로칩을 도입할 계획이 있다고 보고했습니다. 그들이 제공한 정보에 정통한 사람에 따르면 출처는 구체적이지 않았으며 수백만 개의 마더보드가 매년 미국으로 배송됩니다. 그러나 2014년 상반기에 고위급 토론에 대해 브리핑을 받은 다른 사람은 정보 관리들이 더 구체적인 것을 가지고 백악관에 갔다고 말했습니다.

정보의 특수성은 놀라웠지만 그 정보가 제기한 도전 과제도 마찬가지였습니다. Supermicro의 고객에게 광범위한 경고를 발행하는 것은 미국의 주요 하드웨어 제조업체인 회사를 불구로 만들 수 있었고 정보 기관에서는 이 작업이 누구를 목표로 했는지 또는 궁극적인 목표가 무엇인지 명확하지 않았습니다. 게다가, 공격을 받은 사람이 있다는 확인도 없이 FBI는 대응할 수 있는 방법이 제한적이었습니다. 백악관은 정보가 들어오는 대로 정기적인 업데이트를 요청했다고 논의에 정통한 사람이 말했습니다.

타임라인에 정통한 사람에 따르면 Apple은 이상한 네트워크 활동과 펌웨어 문제를 감지한 후 2015년 5월경 Supermicro 서버 내부에서 의심스러운 칩을 발견했습니다. 두 명의 고위 Apple 내부자는 회사가 이 사건을 FBI에 보고했지만 내부적으로라도 기밀로 감지된 내용에 대한 세부 정보를 보관했다고 말했습니다. 한 미국 관리에 따르면, 정부 조사관은 아마존이 이를 발견하고 파괴된 하드웨어에 대한 액세스 권한을 제공했을 때 여전히 스스로 단서를 쫓고 있었습니다. 이는 정보 기관과 FBI가 사이버 및 방첩 팀이 주도하는 전체 조사를 실행하여 칩이 어떻게 생겼고 어떻게 작동하는지 확인할 수 있는 귀중한 기회를 제공했습니다.

Elemental 서버의 칩은 제3자 보안 계약자가 Amazon을 위해 준비한 자세한 보고서를 본 한 사람과 Elemental 서버의 디지털 사진과 X선 이미지를 본 두 번째 사람에 따르면 최대한 눈에 띄지 않게 설계되었습니다. 이 칩은 Amazon의 보안 팀이 준비한 이후 보고서에 통합되었습니다. 회색 또는 회백색의 이 제품은 마이크로칩이라기보다 일반적인 마더보드 구성요소인 신호 조절 커플러에 더 가깝기 때문에 특수 장비 없이는 감지할 수 없었습니다. 보드 모델에 따라 칩의 크기가 약간씩 다르며, 이는 공격자가 다른 공장에 서로 다른 배치를 공급했음을 시사합니다.