Stalked by your digital doppelganger? 디지털도플갱어의 스토킹

Stalked by your digital doppelganger?

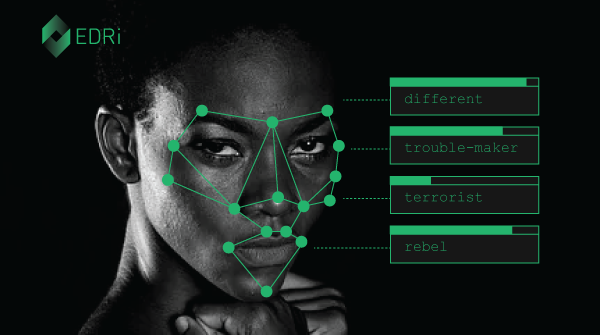

In this fourth installment of EDRi’s facial recognition and fundamental rights series, we explore what could happen if facial recognition collides with data-hungry business models and 24/7 surveillance.

By EDRi · January 29, 2020

In the business of violating privacy

Online platforms, advertisers and data brokers already rely on amassing vast amounts of intimate user data, which they use to sell highly-targeted adverts and to “personalise” services. This is not a by-product of what they do: data monetisation is the central purpose of the Facebooks and Googles of the world.

The Norwegian Consumer Council released a report on the extent of the damage caused by these exploitative and often unlawful ad-tech ecosystems. In fact, many rights violations are exacerbated by data-driven business models, which are systemically opaque, intrusive and designed to grab as much personal data as possible. We’ve all heard the saying: “if the product is free, then you’re the product.”

Already, your interactions build an eerie (and often inaccurate and biased) digital portrait every time you send an email, swipe right or browse the web. And now, through the dystopianly-named “BioMarketing”, advertisers can put cameras on billboards which instantly analyse your face as you walk by, in order to predict your age, gender – and even your ethnicity or mood. They use this data to “personalise” the adverts that you see. So should you be worried that this real-time analysis could be combined with your online interactions? Is your digital doppelganger capable of stepping off your screen and into the street?

When your digital doppelganger turns against you

Airbnb’s discrimination against sex workers is just one example of how companies already use data from other platforms to unjustly deny services to users who, in accessing the service, have breached neither laws nor terms of service. As thousands of seemingly innocuous bits of data about you from your whole digital footprint – and now even your doorbell – are combined, inferences and predictions about your beliefs, likes, habits or identity can be easily used against you.

The recent Clearview AI scandal has cast light on a shady data company, unlawfully scraping and analysing billions of facial images from social media and other platforms and then selling this to police departments. Clearview AI’s systems were sold on the basis of false claims of effectiveness, and deployed by law enforcement with flagrant disregard for data protection, security, safeguards, accuracy or privacy. The extent of online data-gathering and weaponisation may be even worse than we thought.

Surveillance tech companies are cashing in on this biometric recognition and data hype. Spain’s Herta Security and the Netherlands’ VisionLabs are just two of the many companies using the tired (and de-bunked) “security” excuse to justify scanning everyone in shops, stations or even just walking down the street. They sell real-time systems designed to exclude “bad” people by denying them access to spaces, and reward “good” people with better deals. Worryingly, this privatises decisions that have a serious impact on fundamental rights, and enables private companies to act as judge, jury and executioner of our public spaces.

It gets worse…

Surveillance tech companies are predictably evasive about where they get their data and how they train their systems. Although both Herta Security and VisionLabs advertise stringent data protection compliance, their claims are highly questionable: Herta Security, for instance, proudly offers to target adverts based on skin colour. VisionLabs, meanwhile, say that their systems can identify “returning visitors”. It’s hard to see how they could do this without holding on to personally-identifiable biometric data without people’s consent (which would, of course, be a serious breach of data protection law).

As if this wasn’t enough, VisionLabs also enthusiastically offer to analyse the emotions of shoppers. This so-called “affect recognition” is becoming increasingly common, and is based on incredibly dubious scientific and ethical foundations. But that hasn’t stopped it being used to assess everything from whether migrants are telling the truth in immigration interviews to someone’s suitability for a job.

Aren’t we being a bit paranoid?

In theory, a collision of biometric analysis with vast data sources and 24/7 surveillance is terrifying. But would anyone really exploit your online and biometric data like this?

Thanks to facial recognition, many online platforms already know exactly what you look like, and covertly assign highly-specific categories to your profile for advertising purposes. They know if you’re depressed or have a sexually-transmitted disease. They know when you had your last period. They know if you are susceptible to impulse buys. They infer if you are lonely, or have low self-esteem.

There is evidence, too, that facial recognition systems at international borders have now been combined with predictions scraped from covert data sources in order to label travellers as potential terrorists or undocumented migrants. Combine this with the fact that automated systems consistently assess black people as more criminal than white people, even if all other variables are controlled. Your digital doppelganger – inaccuracies, discriminatory judgements and all – becomes indelibly tied to your face and body. This will help law enforcement to identify, surveil, target and control even innocent people.

The violation of your fundamental rights

Given the huge impact that biometric identification systems have on our private lives, the question is not only how they work, but whether they should be allowed to. This data-driven perma-surveillance blurs the boundary between public and private control in dangerous ways, allowing public authorities to outsource responsibility to commercially-protected algorithms, and enabling private companies to commodify people and sell this back to law enforcement. This whole ecosystem fundamentally violates human dignity, which is essential to our ability to live in security and with respect for our private lives.

The ad-tech industry is a treasure trove for biometric surveillance tech companies, who can secretly purchase the knowledge, and therefore the power, to control your access to and interactions with streets, supermarkets and banks based on what your digital doppelganger says about you, whether true or not. You become a walking, tweeting advertising opportunity and a potential suspect in a criminal database. So the real question becomes: when will Europe put its foot down?

디지털 도플갱어의 스토킹?

EDri의 안면 인식 및 기본권 시리즈의 네 번째 기사에서는 안면 인식이 데이터를 많이 사용하는 비즈니스 모델 및 연중무휴 감시와 충돌할 경우 어떤 일이 발생할 수 있는지 살펴봅니다.

작성자: EDRi · 2020년 1월 29일

개인정보를 침해하는 사업에

온라인 플랫폼, 광고주 및 데이터 브로커는 이미 고도로 타겟팅된 광고를 판매하고 서비스를 "개인화"하는 데 사용하는 방대한 양의 친밀한 사용자 데이터를 축적하는 데 의존하고 있습니다. 이것은 그들이 하는 일의 부산물이 아닙니다. 데이터 수익화는 전 세계 Facebook과 Google의 중심 목적 입니다.

노르웨이 소비자 위원회는 이러한 착취적이고 종종 불법적인 광고 기술 생태계로 인한 피해 규모에 대한 보고서 를 발표했습니다 . 사실, 많은 권리 침해는 시스템적으로 불투명 하고 방해가 되며 가능한 한 많은 개인 데이터를 수집하도록 설계된 데이터 중심 비즈니스 모델에 의해 악화 됩니다 . 우리 모두는 "제품이 무료라면 당신도 제품이다"라는 말을 들어본 적이 있습니다.

이미 이메일을 보내거나 오른쪽으로 스와이프하거나 웹을 탐색할 때마다 상호 작용이 으스스한(그리고 종종 부정확하고 편향된) 디지털 초상화를 만듭니다. 그리고 이제 디스토피아적으로 명명된 " BioMarketing "을 통해 광고주는 광고판에 카메라를 설치하여 걸어가는 동안 즉시 얼굴을 분석하여 나이, 성별, 심지어 민족성 또는 기분까지 예측할 수 있습니다. 그들은 이 데이터를 사용하여 귀하가 보는 광고를 "개인화"합니다. 이 실시간 분석이 온라인 상호 작용과 결합될 수 있다는 점에 대해 걱정해야 합니까? 디지털 도플갱어가 화면을 벗어나 거리로 나갈 수 있습니까?

디지털 도플갱어가 당신에게 등을 돌릴 때

Airbnb의 성노동자 차별 은 기업이 이미 다른 플랫폼의 데이터를 사용하여 서비스에 액세스할 때 법률이나 서비스 약관을 위반하지 않은 사용자에 대한 서비스를 부당하게 거부하는 방법의 한 예일 뿐입니다. 전체 디지털 발자국( 지금은 초인종) 에서 겉보기에 무해해 보이는 수천 개의 데이터 가 결합되면 믿음, 좋아하는 것, 습관 또는 정체성에 대한 추론과 예측이 쉽게 사용될 수 있습니다.

최근 Clearview AI 스캔들로 인해 소셜 미디어 및 기타 플랫폼에서 수십억 개의 얼굴 이미지를 불법적으로 분석한 다음 이를 경찰서에 판매 하는 그늘진 데이터 회사가 밝혀 졌습니다. Clearview AI의 시스템은 유효성에 대한 잘못된 주장 을 기반으로 판매되었으며 데이터 보호, 보안, 안전 장치, 정확성 또는 개인 정보 보호에 대한 명백한 무시와 함께 법 집행 기관에 의해 배포되었습니다. 온라인 데이터 수집 및 무기화의 범위는 우리가 생각한 것보다 훨씬 더 나쁠 수 있습니다.

감시 기술 회사는 이러한 생체 인식 및 데이터 과대 광고에 돈을 쓰고 있습니다. 스페인의 Herta Security 와 네덜란드의 VisionLabs 는 상점, 역에 있는 모든 사람을 스캔하거나 심지어 거리를 걸어가는 것을 정당화하기 위해 피곤한(그리고 해명된 ) "보안" 구실 을 사용하는 많은 회사 중 두 곳일 뿐입니다. 그들은 공간에 대한 접근을 거부함으로써 "나쁜" 사람들을 배제하고 더 나은 거래로 "좋은" 사람들에게 보상하도록 설계된 실시간 시스템을 판매합니다. 걱정스럽게도 이것은 기본권에 심각한 영향을 미치는 결정을 사유화하고 민간 기업이 우리 공공 장소의 판사, 배심원 및 집행자 역할을 할 수 있도록 합니다.

악화된다…

감시 기술 회사는 데이터를 어디에서 얻고 어떻게 시스템을 교육하는지 예측할 수 없을 정도로 회피합니다. Herta Security와 VisionLabs 모두 엄격한 데이터 보호 준수를 광고하지만 그들의 주장은 매우 의심스럽습니다.

예를 들어 Herta Security 는 피부색을 기반으로 광고 를 타겟팅 한다고 자랑스럽게 제안합니다 . 한편 VisionLabs는 시스템이 "재방문자"를 식별할 수 있다고 말합니다. 사람들의 동의 없이 개인 식별이 가능한 생체 데이터를 보유하지 않고 어떻게 이를 수행할 수 있는지 알기 어렵습니다(물론 이는 심각한 데이터 보호법 위반임).

이것으로 충분하지 않다는 듯 VisionLabs도 열정적으로 쇼핑객의 감정을 분석합니다. 이 소위 "정동 인식"은 점점 보편화되고 있으며 믿을 수 없을 정도로 모호한 과학적 윤리적 토대를 기반으로 합니다.

그러나 그것은 이민자들이 이민자 면접에서 진실을 말하고 있는지부터(뇌파를 사용한 거짓말 탐지기) 직업에 대한 누군가의 적합성에 이르기까지 모든 것을 평가하는 데 사용되는 것을 멈추지는 못했읍니다.

우리가 약간 편집증적이지 않습니까?

이론상, 방대한 데이터 소스와 연중무휴 감시와 생체 분석의 충돌은 끔찍합니다. 그러나 누군가가 실제로 이와 같이 온라인 및 생체 인식 데이터를 악용할 수 있습니까?

안면 인식 덕분에 많은 온라인 플랫폼에서 이미 귀하가 어떻게 생겼는지 정확히 알고 있으며 광고 목적으로 프로필에 매우 구체적인 카테고리를 은밀하게 할당합니다. 그들은 당신이 우울 하거나 성병 이 있는지 알고 있습니다 . 그들은 당신의 마지막 생리가 언제인지 알고 있습니다. 그들은 당신이 충동 구매에 민감한지 알고 있습니다. 그들은 당신이 외롭거나 자존감이 낮은지 추론합니다 .

이 증거는 국경에서의 얼굴 인식 시스템은 이제 잠재적 인 테러리스트나 불법 이민자로 라벨 여행객하기 위해 비밀 데이터 소스에서 긁어 예측과 결합되었는지도. 자동화된 시스템이 다른 모든 변수가 통제되더라도 흑인을 백인보다 더 범죄자로 일관되게 평가 한다는 사실과 이를 결합합니다 . 당신의 디지털 도플갱어는 부정확성, 차별적 판단 등 모든 것이 당신의 얼굴과 몸에 떼려야 뗄 수 없는 관계가 됩니다. 이것은 법 집행 기관이 무고한 사람들 을 식별, 감시, 표적화 및 통제하는 데 도움이 될 것 입니다.

기본권 침해

생체 인식 시스템이 우리의 사생활에 미치는 막대한 영향을 감안할 때 문제는 작동 방식뿐만 아니라 허용되어야 하는지 여부입니다.

이 데이터 기반 영구 감시는 위험한 방식으로 공적 통제와 사적 통제 간의 경계를 모호하게 하여 공공 기관이 책임을 상업적으로 보호되는 알고리즘에 아웃소싱할 수 있도록 하고 민간 기업이 사람을 상품화하고 이를 법 집행 기관에 다시 판매할 수 있도록 합니다. 이 전체 생태계는 근본적으로 인간의 존엄성을 침해하며, 이는 우리가 안전하게 생활하고 사생활을 존중하는 능력에 필수적입니다.

광고 기술 산업은 디지털 도플갱어가 귀하에 대해 말하는 내용을 기반으로 거리, 슈퍼마켓 및 은행에 대한 액세스 및 상호 작용을 제어할 수 있는 지식과 권한을 비밀리에 구매할 수 있는 생체 인식 감시 기술 회사의 보물창고입니다. 사실이든 아니든. 당신은 걷고, 트윗하는 광고 기회와 범죄 데이터베이스의 잠재적인 용의자가 됩니다. 따라서 진정한 질문은 다음과 같습니다. 유럽은 언제 발을 들일 것입니까?

Facial recognition and fundamental rights 101

This is the first post in a series about the fundamental rights impacts of facial recognition. Private companies and governments worldwide are already experimenting with facial recognition technology. Individuals, lawmakers, developers - and everyone in between - should be aware of the rise of facial recognition, and the risks it poses to rights to privacy, freedom, democracy and non-discrimination.

By EDRi · December 4, 2019

In November 2019, an online search on “facial recognition” churned up over 241 million hits – and the suggested results imply that many people are unsure about what facial recognition is and whether it is legal. Although the first uses that come to mind might be e-passport gates or phone apps, facial recognition has a much broader and more complex set of applications, and is becoming increasingly ubiquitous in both public and private spaces – which can impact a wide range of fundamental rights.

What the tech is facial recognition all about?

Biometrics is the process that makes data out of the human body – literally, your unique “bio”-logical qualities become “metrics.” Facial recognition is a type of biometric application which uses statistical analysis and algorithmic predictions to automatically measure and identify people’s faces in order to make an assessment or decision.

Facial recognition can broadly be categorised in terms of the increasing complexity of the analytics used: from verifying a face (this person matches their passport photo); identifying a face (this person matches someone in our database), to classifying a face (this person is young). Not all uses of facial recognition are the same and, therefore, neither are the associated risks.

Facial recognition can be done live (e.g. analysis of CCTV feeds to see if someone on the street matches a criminal in a police database) or non-live (e.g. matching two photos), which has a higher rate of accuracy.

There are opportunities for error and inaccuracy in each category of facial recognition, with classification being the most controversial because it claims to judge a person’s gender, race, or other characteristics. This categorisation can lead to assessments or decisions that infringe on the dignity of gender non-conforming people, embed harmful gender or racial stereotypes, and lead to unfair and discriminatory outcomes.

Furthermore, facial recognition is not about facts. According to the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), “an algorithm never returns a definitive result, but only probabilities” – and the problem is exacerbated as the data on which that the probabilities are based reflects social biases. When these statistical likelihoods are interpreted as if they are a neutral certainty, this can threaten important rights to fair and due process. This in turn has an impact on individuals’ ability to seek justice when facial recognition infringes on their rights. Digital rights NGOs warn that facial recognition can harm privacy, security and access to services, especially for marginalised communities. A powerful example of this is when facial recognition is used in migration and asylum systems.

A question of social justice and democracy

Whilst discrimination resulting from technical issues or biased data-sets is a genuine problem, accuracy is not the crux of why facial recognition is so concerning. A facial recognition system claiming to identify terrorists at an airport, for example, could be considered 99% accurate even if it did not correctly identify a single terrorist. And greater accuracy is not necessarily the answer either, as it can make it easier for police to target or profile people of colour based on damaging racialised stereotypes.

The real heart of the problem lies in what facial recognition means for our societies, including how it amplifies existing inequalities and violations, and whether it fits with our conceptions of democracy, freedom, privacy, equality, and social good.

Facial recognition by definition raises questions about the balance of personal data protection, mass surveillance, commercial interests and national security which societies should carefully consider. Technology is frequently incredible, impressive, and efficient – but this should not be confused with its use being necessary, beneficial, or useful for us as a society. Unfortunately, these important questions and key issues are often decided out of public sight, with little accountability and oversight.

What’s in a face?

Your face has a particular sensitivity in the context of surveillance, says France’s data protection watchdog – and as a very personal form of personal data, both live and non-live images of your face are already protected from unlawful processing under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Unlike a password, your face is unique to you. Passwords can be kept out of sight and reset if needed – but your face cannot. If your eye is hacked, for example, there is no way to wipe the slate clean. And your face is also distinct from other forms of biometric data such as fingerprints because it is almost impossible to avoid being subject to facial surveillance when such technology is used in public places. Unlike having your fingerprints taken, your face can be surveilled and analysed without your knowledge.

Your face can also be a marker of protected characteristics under international law such as your right to freely practice your religion. For these reasons, facial recognition is highly intrusive and can infringe on rights to privacy and personal data protection, among many other rights.

Researchers have highlighted the frightening assumptions underpinning much of the current hype about facial recognition, especially when used to categorise emotions or qualities based on individuals’ facial movements or dimensions. This harks back to the discredited pseudo-science of physiognomy – a favourite of Nazi eugenicists – and can have massive implications on individuals’ safety and dignity when used to make a judgement about things like their sexuality or whether they are telling the truth about their immigration status. Its use in recruitment also increases discrimination against people with disabilities. Experts warn that there is no scientific basis for these assertions – but that has not stopped tech companies churning out facial classification systems. When used in authoritarian societies or where being LGBTQI+ is a crime, this sort of mass surveillance threatens the lives of journalists, human rights defenders, and anyone that does not conform – which in turn threatens everyone’s freedom.

Why can’t we open the Black Box?

The statistical analysis underpinning facial recognition and other similar technology is often referred to as a “black box”. Sometimes this is because the technological complexity of deep learning systems means that even data scientists do not fully understand the way that the algorithmic models make decisions. Other times, this is because the private companies creating the systems use intellectual property or other commercial protections to hide their models. This means that individuals and even states are prevented from scrutinising the inner workings and decision-making processes of facial recognition tech, even though it impacts so many fundamental rights, which violates principles of transparency and informed consent.

Facial recognition and the rule of law

If this article has felt like a roll-call of human rights violations – that’s because it is. Mass surveillance through facial recognition technology threatens not just the right to privacy, but also democracy, freedom, and the opportunity to develop one’s self with dignity, autonomy and equality in society.

It can have what is known as a “chilling effect” on legal dissent, stifling legitimate criticism, protest, journalism and activism by creating a culture of fear and surveillance in public spaces. Different uses of facial recognition will have different rights implications – depending not only on what and why they are analysing people’s faces, but also because of the justification for the analysis. This includes whether the system meets legal requirements for necessity and proportionality – which, as the next article in this series will explore, many current applications do not.

The rule of law is of vital importance across the European Union, applying to both national institutions and private companies – and facial recognition is no exception. The EU can contribute to protecting people from the threats of facial recognition by strongly enforcing GDPR and by considering how existing or future legislation may impact upon facial recognition too. The EU should foster debates with citizens and civil society to help illuminate important questions including the differences between state and private uses of facial recognition and the definition of public spaces, and undertake research to better understand the human rights implications of the wide variety of uses of this technology. Finally, prior to deploying facial recognition in public spaces, authorities need to produce human rights impact assessments and ensure that the use passes the necessity and proportionality test.

When it comes to facial recognition, just because we can use it does not necessarily mean that we should. But what if we continue to be seduced by the allure of facial recognition? Well, we must be prepared for the violations that arise, implement safeguards for protecting rights, and create meaningful avenues for redress.

안면인식과 기본권 101

이것은 얼굴 인식의 기본적 권리 영향에 대한 시리즈의 첫 번째 게시물입니다. 전 세계의 민간 기업과 정부는 이미 안면 인식 기술을 실험하고 있습니다. 개인, 국회의원, 개발자 및 그 사이의 모든 사람은 안면 인식의 부상과 개인 정보 보호, 자유, 민주주의 및 비차별에 대한 권리에 대한 위험을 인식해야 합니다.

작성자: EDRi · 2019년 12월 4일

2019년 11월에 "안면 인식"에 대한 온라인 검색은 2억 4,100만 건이 넘는 조회수를 기록했습니다. 제안된 결과는 많은 사람들이 안면 인식이 무엇이며 합법인지 확신하지 못한다는 것을 암시합니다. 마음에 떠오르는 첫 번째 용도는 전자 여권 게이트 또는 전화 앱일 수 있지만 얼굴 인식은 훨씬 더 광범위하고 복잡한 응용 프로그램 세트를 가지고 있으며 공공 및 사적 공간 모두에서 점점 더 유비쿼터스해지고 있습니다. 이는 광범위한 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 기본권.

안면 인식 기술은 무엇입니까?

생체 인식은 인체에서 데이터를 만드는 프로세스입니다. 말 그대로 고유한 "생체"-논리적 특성이 "메트릭"이 됩니다. 얼굴 인식은 통계 분석 및 알고리즘 예측을 사용하여 평가 또는 결정을 내리기 위해 사람의 얼굴을 자동으로 측정하고 식별 하는 생체 인식 응용 프로그램 유형입니다 . 안면 인식사용되는 분석의 복잡성 증가 측면에서 다음과 같이 광범위하게 분류할 수 있습니다. 얼굴 확인(이 사람은 여권 사진과 일치); 얼굴 식별(이 사람은 데이터베이스의 누군가와 일치), 얼굴 분류(이 사람은 젊음). 얼굴 인식의 모든 용도가 동일한 것은 아니므로 관련 위험도 마찬가지입니다. 얼굴 인식은 실시간(예: 거리의 누군가가 경찰 데이터베이스의 범죄자와 일치하는지 확인하기 위한 CCTV 피드 분석) 또는 더 높은 정확도의 비실시간(예: 두 장의 사진 일치)으로 수행될 수 있습니다.

기회가 있습니다 오류와 부정확 얼굴 인식의 각 카테고리는 사람의 성별, 인종, 또는 다른 특성을 판단하는 주장 때문에 분류는 가장 논란이되는과. 이 분류는 것을 평가 나 의사 결정으로 이어질 수 있습니다 존엄성에 대한 침해 의 성 부적합 사람들이 유해 성별이나 인종 관념을 포함하고, 불공정하고 차별적 인 결과로 이어집니다.

또한 안면 인식은 사실에 관한 것이 아닙니다. 유럽연합 기본권청(FRA)에 따르면 "알고리즘은 최종 결과를 반환하지 않고 확률만 반환" 하며 확률의 기반이 되는 데이터가 사회적 편견을 반영하기 때문에 문제가 악화됩니다 . 이러한 통계적 가능성이 중립적 확실성인 것처럼 해석되면 공정하고 적법한 절차에 대한 중요한 권리를 위협할 수 있습니다. 이것은 차례로 안면 인식이 자신의 권리를 침해할 때 정의를 추구하는 개인의 능력에 영향을 미칩니다. 디지털 권리 NGO 는 안면 인식이 개인 정보 보호, 보안 및 서비스 액세스에 해를 끼칠 수 있다고 경고 합니다., 특히 소외된 지역 사회를 위해. 이에 대한 강력한 예는 안면 인식이 이주 및 망명 시스템에 사용되는 경우입니다 .

사회 정의와 민주주의의 문제

기술적인 문제나 편향된 데이터 세트로 인한 차별은 진정한 문제이지만 정확성이 얼굴 인식이 중요한 이유의 핵심은 아닙니다. 예를 들어, 공항에서 테러리스트를 식별한다고 주장 하는 얼굴 인식 시스템 은 단일 테러리스트를 정확하게 식별하지 못하더라도 99% 정확 하다고 간주될 수 있습니다 . 경찰이 인종 차별적 고정 관념 을 손상시키는 유색 인종 을 쉽게 표적 으로 삼 거나 프로파일링 할 수 있기 때문에 정확도가 더 높다고 반드시 답은 아닙니다.. 문제의 진정한 핵심은 안면 인식이 기존의 불평등과 위반을 증폭시키는 방법과 민주주의, 자유, 사생활, 평등 및 사회적 선에 대한 우리의 개념에 맞는지 여부를 포함하여 우리 사회에 대한 안면 인식의 의미에 있습니다. 정의에 따른 안면 인식은 사회가 신중하게 고려해야 하는 개인 데이터 보호, 대량 감시, 상업적 이익 및 국가 안보의 균형에 대한 질문을 제기합니다. 기술은 종종 놀랍고 인상적이며 효율적입니다. 그러나 이것을 우리 사회에 필요하거나 유익하거나 유용한 사용과 혼동해서는 안 됩니다. 불행히도 이러한 중요한 질문과 주요 문제는 책임과 감독이 거의 없이 공개적으로 결정되는 경우가 많습니다 .

얼굴에 무엇이 들어 있습니까?

프랑스의 데이터 보호 감시 기관에 따르면 당신의 얼굴은 감시의 맥락에서 특히 민감 합니다. 그리고 매우 개인적인 형태의 개인 데이터로서 당신의 얼굴의 실시간 이미지와 실시간 이미지가 모두 일반 데이터 보호 규정(General Data Protection Regulation)에 따라 불법 처리로부터 이미 보호되고 있습니다. (GDPR).

비밀번호와 달리 얼굴은 고유합니다. 비밀번호는 보이지 않게 하고 필요한 경우 재설정할 수 있지만 얼굴은 그렇지 않습니다. 예를 들어 눈이 해킹당 했다면 슬레이트를 깨끗이 닦을 방법이 없습니다. 또한 얼굴은 지문과 같은 다른 형태의 생체 데이터와 구별됩니다. 이러한 기술을 공공 장소에서 사용할 경우 안면 감시의 대상이 되는 것을 피하기가 거의 불가능하기 때문입니다. 지문을 채취하는 것과 달리 사용자가 모르는 사이에 얼굴을 감시하고 분석할 수 있습니다. 당신의 얼굴은 또한 당신의 종교를 자유롭게 실천할 권리와 같이 국제법에 따라 보호되는 특성의 표시가 될 수 있습니다. 이러한 이유로 안면 인식은 매우 침해적이며 다른 많은 권리 중에서 개인 정보 보호 및 개인 데이터 보호에 대한 권리를 침해할 수 있습니다.

연구원들은 특히 개인의 안면 움직임이나 치수를 기반으로 감정이나 특성을 분류하는 데 사용되는 경우 안면 인식에 대한 현재 과대 광고의 근간이 되는 무서운 가정을 강조했습니다. 이것은 나치 우생학자들이 가장 좋아하는 불명예의 사이비 과학인 생리학을 떠올리게 하며, 개인의 섹슈얼리티나 이민에 대한 진실을 말하고 있는지 여부를 판단하는 데 사용될 때 개인의 안전과 존엄성에 막대한 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 상태 . 채용에 사용하는 것은 또한 장애인에 대한 차별을 증가시킵니다 . 전문가들은 경고이러한 주장에 대한 과학적 근거는 없지만 기술 회사가 안면 분류 시스템을 대량 생산하는 것을 막지는 못했습니다. 권위주의 사회 에서 사용 되거나 LGBTQI+ 가 되는 것이 범죄인 곳에서 이러한 종류의 대규모 감시는 언론인, 인권 옹호자 및 순응하지 않는 모든 사람의 생명을 위협하며, 이는 결국 모든 사람의 자유를 위협합니다.

블랙박스를 열 수 없는 이유는 무엇입니까?

얼굴 인식 및 기타 유사한 기술을 뒷받침하는 통계 분석을 종종 "블랙 박스"라고 합니다. 때로는 딥 러닝 시스템의 기술적 복잡성으로 인해 데이터 과학자도 알고리즘 모델이 결정을 내리는 방식을 완전히 이해하지 못하기 때문입니다. 다른 경우에는 시스템을 만드는 개인 회사가 지적 재산권 또는 기타 상업적 보호를 사용하여 모델을 숨기기 때문입니다. 이는 개인과 국가가 안면 인식 기술의 내부 작동 및 의사 결정 프로세스를 조사하는 것이 금지되어 있음을 의미합니다. 이는 투명성 및 사전 동의의 원칙을 위반하는 많은 기본 권리에 영향을 미치더라도 마찬가지입니다.

얼굴 인식과 법치

이 기사가 인권침해를 호소하는 것처럼 느껴졌다면 - 그 이유입니다. 안면인식 기술을 통한 대량 감시는 사생활의 권리뿐 아니라 민주주의와 자유, 사회에서 존엄성, 자율성, 평등한 자기계발의 기회까지 위협하고 있다. 이는 법적 반대 의견에 "오싹한 효과"로 알려진 것을 가질 수 있으며, 공공 장소에서 공포와 감시의 문화를 조성함으로써 정당한 비판, 항의, 저널리즘 및 행동주의를 억누를 수 있습니다. 얼굴 인식의 다양한 용도는 사람들의 얼굴을 분석하는 대상과 이유뿐만 아니라 분석의 정당성에 따라 권리에 대한 영향이 다릅니다. 여기에는 시스템이 필요성과 비례성에 대한 법적 요구 사항을 충족하는지 여부가 포함됩니다.

법의 지배는 국가 기관과 민간 기업 모두에 적용되는 유럽 연합 전역에서 매우 중요하며 안면 인식도 예외는 아닙니다. EU는 GDPR을 강력하게 시행하고 기존 또는 미래의 법률이 안면 인식에 미치는 영향을 고려하여 안면 인식의 위협으로부터 사람들을 보호하는 데 기여할 수 있습니다. EU는 시민 및 시민 사회와의 토론을 촉진하여 안면 인식의 국가와 민간 사용의 차이점과 공공 장소의 정의를 비롯한 중요한 질문을 조명하고 다양한 사용이 인권에 미치는 영향을 더 잘 이해하기 위한 연구를 수행해야 합니다. 마지막으로, 공공 장소에 얼굴 인식을 배치하기 전에,

얼굴 인식과 관련하여 사용할 수 있다고 해서 반드시 사용해야 하는 것은 아닙니다. 하지만 우리가 계속해서 안면 인식의 유혹에 빠지면 어떻게 될까요? 글쎄요, 우리는 발생하는 위반에 대비해야 하고, 권리를 보호하기 위한 안전 장치를 구현하고, 시정을 위한 의미 있는 길을 만들어야 합니다.

The many faces of facial recognition in the EU

In this second installment of EDRi's facial recognition and fundamental rights series, we look at how different EU Member States, institutions and other countries worldwide are responding to the use of this tech in public spaces.

By EDRi · December 18, 2019

We previously launched the first article and case study in a series exploring the human rights implications of facial recognition technology. In this post, we look at how different EU Member States, institutions and other countries worldwide are responding to the use of this tech in public spaces.

Live facial recognition technology is increasingly used to identify people in public, often without their knowledge or properly-informed consent. Sometimes referred to as face surveillance, concerns about the use of these technologies in public places is gaining attention across Europe. Public places are not well-defined in law, but can include open spaces like parks or streets, publicly-administered institutions like hospitals, spaces controlled by law enforcement such as borders, and – arguably – any other places where people wanting to take part in society have no ability to opt out from entering. As it stands, there is no EU consensus on the legitimacy nor the desirability of using facial recognition in such spaces.

Public face surveillance is being used by many police forces across Europe to look out for people on their watch-lists; for crowd control at football matches in the UK; and in tracking systems in schools (although so far, attempts to do this in the EU have been stopped). So-called “smart cities” – where technologies that involve identifying people are used to monitor environments with the outward aim of making cities more sustainable – have been implemented to some degree in at least eight EU Member States. Outside the EU, China is reportedly using face surveillance to crack down on the civil liberties of pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong, and there are mounting fears that Chinese surveillance tech is being exported to the EU and even used to influence UN facial recognition standards. Such issues have brought facial recognition firmly onto the human rights agenda, raising awareness of its (mis)use by both democratic and authoritarian governments.

How is the EU grappling with the facial recognition challenge?

Throughout 2019, a number of EU Member States responded to the threat of facial recognition, although their approaches reveal many inconsistencies. In October 2019, the Swedish Data Protection Authority (DPA) – the national body responsible for personal data under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – approved the use of facial recognition technology for criminal surveillance, finding it legal and legitimate (subject to clarification of how long the biometric data will be kept). Two months earlier, they levied a fine of 20 000 euro for an attempt to use facial recognition in a school. Similarly, the UK DPA has advised police forces to “slow down” due to the volume of unknowns – but have stopped short of calling for a moratorium. UK courts have failed to see their DPA’s problem with facial recognition, despite citizens’ fears that it is highly invasive. In the only European ruling so far, Cardiff’s high court found police use of public face surveillance cameras to be proportionate and lawful, despite accepting that this technology infringes on the right to privacy.

The French DPA took a stronger stance than the UK’s DPA, advising a school in the city of Nice that the intrusiveness of facial recognition means that their planned face recognition project cannot be implemented legally. They emphasised the “particular sensitivity” of facial recognition due to its association with surveillance and its potential to violate rights to freedom and privacy, and highlighting the enhanced protections required for minors. Importantly, France’s DPA concluded that legally-compliant and equally effective alternatives to face recognition, such as using ID badges to manage student access, can and should be used instead. Echoing this stance, the European Data Protection Supervisor, Wojciech Wiewiórowski, issued a scathing condemnation of facial recognition, calling it a symptom of rising populist intolerance and “a solution in search of a problem.”

A lack of justification for the violation of fundamental rights

However, as in the UK, the French DPA’s views have frequently clashed with other public bodies. For example, the French government is pursuing the controversial Alicem digital identification system despite warnings that it does not comply with fundamental rights. There is also an inconsistency in the differentiation made between the surveillance of children and adults. The reason given by both France and Sweden for rejecting child facial recognition is that it will create problems for them in adulthood. Using this same logic, it is hard to see how the justification for any form of public face surveillance – especially when it is unavoidable, as in public spaces – would meet legal requirements of legitimacy or necessity, or be compliant with the GDPR’s necessarily strict rules for biometric data.

The risks and uncertainties outlined thus far have not stopped Member States accelerating their uptake of facial recognition technology. According to the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA), Hungary is poised to deploy an enormous facial recognition system for multiple reasons including road safety and the Orwellian-sounding “public order” purposes; the Czech Republic is increasing its facial recognition capacity in Prague airport; “extensive” testing has been carried out by Germany and France; and EU-wide migration facial recognition is in the works. EDRi member SHARE Foundation have also reported on its illegal use in Serbia, where the interior ministry’s new system has failed to meet the most basic requirements under law. And of course, private actors also have a vested interest in influencing and orchestrating European face recognition use and policy: lobbying the EU, tech giant IBM has promoted its facial recognition technology to governments as “potentially life-saving” and even funded research that dismisses concerns about the ethical and human impacts of AI as “exaggerated fears.”

As Interpol admits, “standards and best practices [for facial recognition] are still in the process of being created.” Despite this, facial recognition continues to be used in both public and commercial spaces across the EU – unlike in the US, where four cities including San Francisco have proactively banned facial recognition for policing and other state uses, and a fifth, Portland, has started legislative proceedings to ban facial recognition for both public and private purposes – the widest ban so far.

The need to ask the big societal questions

Once again, these examples return to the idea that the problem is not technological, but societal: do we want the mass surveillance of our public spaces? Do we support methods that will automate existing policing and surveillance practices – along with the biases and discrimination that inevitably come with them? When is the use of technology genuinely necessary, legitimate and consensual, rather than just sexy and exciting? Many studies have shown that – despite claims by law enforcement and private companies – there is no link between surveillance and crime prevention. Even when studies have concluded that “at best” CCTV may help deter petty crime in parking garages, this has only been with exceptionally narrow, well-controlled use, and without the need for facial recognition. And as explored in our previous article, there is overwhelming evidence that rather than improving public safety or security, facial recognition creates a chilling effect on a shocking smorgasbord of human rights.

As in the case of the school in Nice, face recognition cannot be considered necessary and proportionate when there are many other ways to achieve the same aim without violating rights. FRA agrees that general reasons of “crime prevention or public security” are neither legitimate nor legal justifications per se, and so facial recognition must be subject to strict legality criteria.

Human rights exist to help redress the imbalance of power between governments, private entities and citizens. In contrast, the highly intrusive nature of face surveillance opens the door to mass abuses of state power. DPAs and civil society, therefore, must continue to pressure governments and national authorities to stop the illegal deployment and unchecked use of face surveillance in Europe’s public spaces. Governments and DPAs must also take a strong stance to the private sector’s development of face surveillance technologies, demanding and enforcing GDPR and human rights compliance at every step.

EU에서 안면 인식의 다양한 얼굴

EDri의 안면 인식 및 기본권 시리즈의 두 번째 기사에서는 전 세계의 다양한 EU 회원국, 기관 및 기타 국가가 공공 장소에서 이 기술을 사용하는 데 어떻게 대응하고 있는지 살펴봅니다.

작성자: EDRi · 2019년 12월 18일

우리는 이전 에 얼굴 인식 기술이 인권에 미치는 영향을 탐구하는 시리즈 의 첫 번째 기사 와 사례 연구 를 시작했습니다 . 이 게시물에서는 전 세계의 다양한 EU 회원국, 기관 및 기타 국가가 공공 장소에서 이 기술을 사용하는 데 어떻게 대응하고 있는지 살펴봅니다.

라이브 안면 인식 기술은 대중이 알지 못하거나 적절한 정보에 입각한 동의 없이 사람들을 식별하는 데 점점 더 많이 사용되고 있습니다. 때로는 얼굴 감시 라고도 하는 공공 장소에서 이러한 기술을 사용하는 것에 대한 우려가 유럽 전역에서 주목받고 있습니다. 공공 장소는 법으로 잘 정의되어 있지 않지만 공원이나 거리와 같은 열린 공간 , 병원과 같은 공공 관리 기관, 국경 과 같이 법 집행 기관이 통제하는 공간 , 그리고 아마도 사람들이 참여하기를 원하는 기타 모든 장소를 포함할 수 있습니다. 사회는 진입을 거부할 수 있는 능력이 없습니다. 현재로서는 그러한 공간에서 안면 인식을 사용하는 것이 합법성이나 바람직함에 대한 EU의 합의가 없습니다.

공개 얼굴 감시는 유럽 전역의 많은 경찰이 감시 목록에 있는 사람들을 찾기 위해 사용하고 있습니다. 영국 축구 경기 에서 군중 통제를 위해 ; 그리고 학교의 추적 시스템에서 (지금까지는 EU에서 이것을 하려는 시도가 중단되었지만). 사람을 식별하는 기술을 사용하여 도시를 더 지속 가능하게 만드는 외부 목표로 환경을 모니터링하는 소위 "스마트 도시"는 최소 8개 EU 회원국에서 어느 정도 구현되었습니다. EU 밖에서 중국이 안면 감시 를 통해 홍콩 민주화 운동가들의 시민적 자유를 탄압하고 있는 것으로 알려지면서 중국의 감시 기술이 수출되고 있다는 우려가 커지고 있다.EU에 적용되고 UN 안면 인식 표준 에 영향을 미치기까지 했습니다 . 이러한 문제는 안면 인식을 인권 의제로 확고히 하여 민주주의 정부와 권위주의 정부 모두에서 안면 인식을 (오용) 사용하는 것에 대한 인식을 높였습니다.

EU는 안면 인식 문제와 어떻게 씨름하고 있습니까?

2019년 내내 많은 EU 회원국이 안면 인식의 위협에 대응했지만 접근 방식은 많은 불일치를 드러냈습니다. 2019년 10월, GDPR(일반 데이터 보호 규정)에 따라 개인 데이터를 책임지는 국가 기관인 스웨덴 데이터 보호국(DPA)은 범죄 감시를 위한 안면 인식 기술의 사용을 승인했으며 합법적이고 합법적이라고 판단했습니다(설명에 따라 생체 인식 데이터가 보관되는 기간). 두 달 전 학교에서 안면인식을 시도한 혐의로 20,000유로 의 벌금 을 부과했습니다 . 마찬가지로 영국 DPA는 경찰에 "속도를 늦추십시오"라고 조언 했습니다.미지의 양으로 인해 – 그러나 모라토리엄을 요구하기에는 이르지 않았습니다. 영국 법원은 DPA가 매우 침습적이라는 시민들의 두려움에도 불구하고 안면 인식과 관련된 DPA의 문제를 보지 못했습니다. 에서 유일한 유럽 지금까지 지배 , 카디프의 고등 법원이 될 공공 얼굴 감시 카메라의 경찰이 사용 발견 비례 합법적를 수용에도 불구하고, 그 개인 정보 보호에 대한 권리에이 기술을 침해.

프랑스 DPA 는 영국의 DPA보다 강력한 입장을 취 하며 니스시의 한 학교에 안면 인식의 방해가 계획된 안면 인식 프로젝트를 합법적으로 구현할 수 없음을 의미한다고 조언했습니다. 그들은 감시와 관련되어 있고 자유와 사생활에 대한 권리를 침해할 가능성이 있기 때문에 안면 인식의 "특별한 민감성"을 강조하고 미성년자에게 요구되는 강화된 보호를 강조했습니다. 중요하게도 프랑스 DPA는 ID 배지를 사용하여 학생 액세스를 관리하는 것과 같이 법적으로 준수되고 동등하게 효과적인 안면 인식 대안을 사용할 수 있고 사용해야 한다고 결론지었습니다. 이러한 입장을 반영하여 유럽 데이터 보호 감독관인 Wojciech Wiewiórowski는 가혹한 규탄을 발표했습니다. 포퓰리스트의 편협함이 증가하는 증상이자 "문제를 찾는 해결책"이라고 부르는 안면 인식의 문제입니다.

기본권 침해에 대한 정당성 부족

그러나 영국과 마찬가지로 프랑스 DPA의 견해는 다른 공공 기관과 자주 충돌했습니다. 예를 들어, 프랑스 정부는 기본권에 어긋난다 는 경고에도 불구하고 논란 이 되고 있는 알리심(Alicem) 전자식별시스템을 추진하고 있다. 어린이 감시와 성인 감시를 구분하는 데에도 불일치가 있습니다. 프랑스와 스웨덴이 아동 안면 인식을 거부한 이유는 성인이 되어서도 문제가 발생하기 때문입니다. 이와 동일한 논리를 사용하여, 특히 공공 장소에서와 같이 불가피한 경우 모든 형태의 공개 안면 감시에 대한 정당화가 합법성 또는 필요성에 대한 법적 요구 사항을 충족하거나 GDPR의 필연적으로 엄격한 규칙을 준수하는지 확인하기 어렵습니다. 생체 데이터용.

지금까지 설명한 위험과 불확실성은 회원국이 안면 인식 기술의 채택을 가속화하는 것을 막지 못했습니다. EU의 FRA(Fundamental Rights Agency)에 따르면 헝가리는 도로 안전 및 오웰식 "공공 질서" 목적을 포함하여 여러 가지 이유로 거대한 안면 인식 시스템을 배치할 태세입니다. 체코는 프라하 공항에서 안면 인식 능력을 늘리고 있습니다. 독일과 프랑스에서 "광범위한" 테스트를 수행했습니다. 그리고 EU 전역의 이주 안면 인식 작업이 진행 중입니다. EDri 회원 SHARE 재단은 또한 세르비아에서 불법 사용 에 대해보고했습니다, 내무부의 새로운 시스템이 법에 따른 가장 기본적인 요건을 충족하지 못하는 경우. 그리고 물론 민간 행위자들도 유럽의 얼굴 인식 사용 및 정책에 영향을 미치고 조정하는 데 기득권이 있습니다. EU에 로비를 하고 기술 대기업인 IBM은 얼굴 인식 기술을 " 잠재적으로 생명을 구할 수 있다 "고 정부에 홍보했으며 심지어 연구를 기각하는 자금을 지원했습니다. AI의 윤리적, 인간적 영향에 대한 우려 는 " 과장된 두려움 "으로 나타납니다.

Interpol이 인정하는 것처럼 "[얼굴 인식을 위한] 표준과 모범 사례는 아직 만들어지는 중입니다." 그럼에도 불구하고 안면 인식은 EU 전역의 공공 및 상업 공간에서 계속 사용됩니다. 샌프란시스코를 포함한 4개 도시 가 치안 및 기타 국가 사용을 위한 안면 인식을 사전에 금지하고 다섯 번째 도시인 포틀랜드 가 시작된 미국과 달리 공적 및 사적 목적 모두에 대한 안면 인식을 금지하기 위한 입법 절차는 지금까지 가장 광범위한 금지 조치입니다.

큰 사회적 질문을 해야 할 필요성

다시 한 번, 이러한 예는 문제가 기술이 아니라 사회적이라는 생각으로 돌아갑니다. 우리는 공공 장소에 대한 대규모 감시를 원합니까? 필연적으로 수반되는 편견과 차별과 함께 기존 치안 및 감시 관행을 자동화하는 방법을 지원 합니까? 단순히 섹시하고 흥미진진한 것이 아니라 기술을 사용하는 것이 진정으로 필요하고 합법적이며 합의된 때는 언제입니까? 많은 연구 에 따르면 법 집행 기관과 민간 기업의 주장에도 불구하고 감시와 범죄 예방 사이 에는 연관성 이 없습니다 . 심지어 연구는 결론을 내렸다 때 "라는 최고의 "CCTV가 억제 도움이 될 수 있습니다 주차장에서 사소한 범죄를, 이것은 예외적으로 좁고 잘 제어된 사용과 안면 인식의 필요 없이만 사용되었습니다. 그리고 우리의 이전 기사에서 살펴본 것처럼 , 안면 인식이 공공 안전이나 보안을 개선하기보다는 충격적인 인권 문제에 오싹한 영향을 미친다 는 압도적인 증거 가 있습니다.

니스에 있는 학교의 경우처럼 권리를 침해하지 않고 동일한 목적을 달성할 수 있는 다른 방법이 많이 있을 때 얼굴 인식은 필요하고 적절하다고 볼 수 없습니다 . FRA 는 "범죄 예방 또는 공안"의 일반적인 이유는 그 자체로 합법적이거나 법적 정당성이 아니므로 안면 인식은 엄격한 합법성 기준을 따라야 한다는 데 동의 합니다.

인권은 정부, 민간 단체 및 시민 간의 권력 불균형을 시정하기 위해 존재합니다. 대조적으로, 안면 감시의 고도로 침입적인 특성은 국가 권력의 대량 남용의 문을 엽니다. 따라서 DPA와 시민 사회는 정부와 국가 당국에 유럽의 공공 장소에서 불법 배치와 확인되지 않은 안면 감시의 사용을 중단하도록 계속 압력을 가해야 합니다. 정부와 DPA는 또한 민간 부문의 안면 감시 기술 개발에 대해 강력한 입장을 취하여 모든 단계에서 GDPR 및 인권 준수를 요구하고 시행해야 합니다.

Your face rings a bell: Three common uses of facial recognition

Not all applications of facial recognition are created equal. In this third installment, we sift through the hype to analyse three increasingly common uses of facial recognition: tagging pictures on Facebook, automated border control gates, and police surveillance.

By EDRi · January 15, 2020

Not all applications of facial recognition are created equal. As we explored in the first and second instalments of this series, different uses of facial recognition pose distinct but equally complex challenges. Here we sift through the hype to analyse three increasingly common uses of facial recognition: tagging pictures on Facebook, automated border control gates, and police surveillance.

The chances are that your face has been captured by a facial recognition system, if not today, then at least in the last month. It is worryingly easy to stroll through automated passport gates at an airport, preoccupied with the thought of seeing your loved ones, rather than consider potential threats to your privacy. And you can quite happily walk through a public space or shop without being aware that you are being watched, let alone that your facial expressions might be used to label you a criminal. Social media platforms increasingly employ facial recognition, and governments around the world have rolled it out in public. What does this mean for our human rights? And is it too late to do something about it?

First: What the f…ace? – Asking the right questions about facial recognition!

As the use of facial recognition skyrockets, it can feel that there are more questions than answers. This does not have to be a bad thing: asking the right questions can empower you to challenge the uses that will infringe on your rights before further damage is done.

A good starting point is to look at impacts on fundamental rights such as privacy, data protection, non-discrimination and freedoms, and compliance with international standards of necessity, remedy and proportionality. Do you trust the owners of facial recognition systems (or indeed other types of biometric recognition and surveillance) whether public or private, to keep your data safe and to use it only for specific, legitimate and justifiable purposes? Do they provide sufficient evidence of effectiveness, beyond just the vague notion of “public security”?

Going further, it is important to ask societal questions like: does being constantly watched and analysed make you feel safer, or just creeped out? Will biometric surveillance substantially improve your life and your society, or are there less invasive ways to achieve the same goals?

Looking at biometric surveillance in the wild

As explored in the second instalment of this series, many public face surveillance systems have been shown to violate rights and been deemed illegal by data protection authorities. Even consent-based, optional applications may not be as unproblematic as they first seem. This is our “starter for ten” for thinking through the potentials and risks of some increasingly common uses of facial verification and identification – we’ll be considering classification and other biometrics next time. Think we’ve missed something? Tweet us your ideas @edri using #FacialRecognition.

Automatic tagging of pictures on Facebook

Facebook uses facial recognition to tag users in pictures, as well as other “broader” uses. Under public pressure, in September 2019, they made it opt-in – but this applies only to new, not existing, users.

Potentials:

- Saves time compared to manual tagging

- Alerts you when someone has uploaded a picture of you without your knowledge

Risks:

- The world’s biggest ad-tech company can find you on photos or videos across the web – forever

- Facebook will automatically scan, analyse and categorise every photo uploaded

- You will automatically be tagged in photos you might want to avoid

- Errors especially for people with very light or very dark skin

Evidence:

- Facebook has been training algorithms using Instagram photos and then selling them

- Facebook tagging is 98% accurate – but with 2.4bn users, that 2% amounts to hundreds of millions of errors, especially for people of colour

Creepy, verging on dystopian, especially as the feature is on by default for some users (here’s how to turn it off: https://www.cnet.com/news/neons-ceo-explains-artificial-humans-to-me-and-im-more-confused-than-ever/). We’ll leave it to you to decide if the potentials outweigh the risks.

Automated border control (ePassport gates)

Automated border control (ABC) systems, sometimes known as e-gates or ePassport gates, are self-serve systems that authenticate travellers against their identity documents – a type of verification.

Potentials:

- Suggested as a solution for congestion as air travel increases

- Matches you to your passport, rather than a central database – so in theory your data isn’t stored

Risks:

- Longer queues for those who cannot or do not want to use it

- Lack of evidence that it saves time overall

- Difficult for elderly passengers to use

- May cause immigration issues or tax problems

- Normalises face recognition

- Disproportionately error-prone for people of colour, leading to unjustified interrogations

- Supports state austerity measures

Evidence:

- Stats vary wildly, but credible sources suggest the average border guard takes 10 seconds to process a traveler, faster than the best gates which take 10-15 seconds

- Starting to be used in conjunction with other data to predict behaviour

- High volume of human intervention needed due to user or system errors

- Extended delays for the 5% of people falsely rejected

- Evidence of falsely criminalising innocent people

- Evidence of falsely accepting people with wrong passport

Evidence of effectiveness can be contradictory, but the impacts – especially on already marginalised groups – and the ability to combine face data with other data to induce additional information about travellers bear major potential for abuse. We suspect that offline solutions such as funding more border agents and investing in queue management could be equally efficient and less invasive.

Police surveillance

Sometimes referred to as face surveillance, police forces across Europe – often in conjunction with private companies – are using surveillance cameras to perform live identification in public spaces.

Potentials:

- Facilitates the analysis of video recordings in investigations

Risks:

- Police hold a database of faces and are able to track and follow every individual ever scanned

- Replaces investment in police recruitment and training

- Can discourage use of public spaces – especially those who have suffered disproportionate targeting

- Chilling effect on freedom of speech and assembly, an important part of democratic participation

- May also rely on pseudo-scientific emotion “recognition”

- Legal ramifications for people wrongly identified

- No ability to opt out

Evidence:

- UK police force says face recognition is helping make up for budget cuts

- Effectiveness of surveillance is nearly impossible to prove

- Evidence of law enforcement abuse of access to data

- Automates existing policing biases and racial profiling

- Makes legitimate anonymous protests impossible

- Undermines privacy rights, making us less free

Increased public security could be achieved by measures to tackle issues such as inequality or antisocial behaviour or generally investing in police capability rather than surveillance technology.

Facing reality: towards a mass surveillance society?

Without intervention, facial recognition is on a path to omniscience. In this post, we have only scratched the surface. However, these examples identify some of the different actors that may want to collect and analyse your face data, what they gain from it, and how they may (ab)use it. They have also shown that benefits of facial surveillance are frequently cost-cutting reasons, rather than user benefit.

We’ve said it before: tech is not neutral. It reflects and reinforces the biases and world views of its makers. The risks are amplified when systems are deployed rapidly, without considering the big picture or the slippery slope towards authoritarianism. The motivations behind each use must be scrutinised and proper assessments carried out before deployment. As citizens, it is our right to demand this.

Your face has a significance beyond just your appearance – it is a marker of your unique identity and individuality. But with prolific facial recognition, your face becomes a collection of data points which can be leveraged against you and infringe on your ability to live your life in safety and with privacy. With companies profiting from the algorithms covertly built using photos of users, faces are literally commodified and traded. This has serious repercussions on our privacy, dignity and bodily integrity.

당신의 얼굴은 종을 울립니다: 얼굴 인식의 세 가지 일반적인 용도

얼굴 인식의 모든 응용 프로그램이 동일하게 만들어지는 것은 아닙니다. 이 세 번째 기사에서는 페이스북의 사진에 태그 지정, 자동화된 국경 통제 게이트, 경찰 감시와 같이 점점 더 일반적으로 사용되는 안면 인식의 세 가지 용도를 분석하기 위해 과장된 내용을 살펴봅니다.

작성자: EDRi · 2020년 1월 15일

얼굴 인식의 모든 응용 프로그램이 동일하게 만들어지는 것은 아닙니다. 이 시리즈 의 1부 와 2 부 에서 살펴보았듯이 얼굴 인식의 다양한 사용은 뚜렷하지만 똑같이 복잡한 문제를 제기합니다. 여기에서 우리는 페이스북에 사진에 태그하기, 자동화된 국경 통제 게이트, 경찰 감시와 같이 점점 더 일반적으로 사용되는 안면 인식의 세 가지 용도를 분석하기 위해 과장된 내용을 살펴봅니다.

당신의 얼굴이 얼굴 인식 시스템에 의해 포착되었을 가능성이 있습니다. 오늘은 아니더라도 적어도 지난 달에는 가능합니다. 공항의 자동 여권 게이트를 거닐며 사생활에 대한 잠재적인 위협을 고려하기보다 사랑하는 사람을 볼 생각에 몰두하는 것은 걱정스러울 정도로 쉽습니다. 그리고 당신 의 표정이 당신을 범죄자로 낙인찍는 데 사용될 수 있다는 것은 고사하고, 당신이 감시당하고 있다는 것을 의식하지 않고 공공 장소 나 상점 을 아주 행복하게 걸을 수 있습니다. 소셜 미디어 플랫폼은 점점 더 안면 인식을 사용하고 있으며 전 세계 정부 는 이를 공개적으로 시행하고 있습니다. 이것이 우리 인권에 의미하는 바는 무엇입니까? 그리고 그것에 대해 무언가를 하기에는 너무 늦었습니까?

첫 번째: 무슨...얼굴? – 안면인식에 대한 올바른 질문!

안면인식 활용이 급증하면서 답보다 질문이 더 많다는 것을 느낄 수 있다. 이것이 꼭 나쁜 것은 아닙니다. 올바른 질문을 하면 추가 피해가 발생하기 전에 귀하의 권리를 침해할 사용에 대해 이의를 제기할 수 있습니다.

좋은 출발점은 프라이버시, 데이터 보호, 차별 금지 및 자유와 같은 기본 권리에 대한 영향과 필요성, 구제 및 비례에 대한 국제 표준 준수를 살펴보는 것입니다. 공개 또는 비공개 얼굴 인식 시스템(또는 다른 유형 의 생체 인식 및 감시) 소유자를 신뢰 하여 데이터를 안전하게 유지하고 특정하고 합법적이며 정당한 목적으로만 사용합니까? 그들은 "공안"의 막연한 개념을 넘어 효과에 대한 충분한 증거를 제공합니까?

더 나아가, 다음과 같은 사회적 질문을 하는 것이 중요합니다. 지속적으로 관찰되고 분석되는 것이 더 안전하다고 느끼는가 아니면 그냥 소름이 돋는가? 생체 인식 감시가 귀하의 삶과 사회를 실질적으로 개선할 것입니까? 아니면 동일한 목표를 달성하기 위한 덜 침습적인 방법이 있습니까?

야생에서의 생체 인식 감시

이 시리즈 의 두 번째 기사 에서 살펴본 것처럼 많은 공개 안면 감시 시스템이 권리를 침해하는 것으로 나타났으며 데이터 보호 당국에 의해 불법으로 간주되었습니다. 동의 기반의 선택적 응용 프로그램도 처음 보이는 것처럼 문제가 되지 않을 수 있습니다. 이것은 점점 더 일반적으로 사용되는 안면 확인 및 식별의 가능성과 위험에 대해 생각하기 위한 "10분의 시작"입니다. 다음 시간에는 분류 및 기타 생체 인식을 고려할 것입니다. 우리가 뭔가를 놓친 것 같아요? #FacialRecognition을 사용하여 @edri에 아이디어를 트윗하세요.

Facebook에서 사진에 자동 태그 지정

Facebook은 얼굴 인식을 사용하여 사진에서 사용자를 태그하고 기타 " 광범위한 " 용도로 사용합니다. 대중의 압력에 따라 2019년 9월에 옵트인으로 만들었습니다. 그러나 이는 기존 사용자가 아닌 신규 사용자에게만 적용됩니다.

잠재력:

- 수동 태깅에 비해 시간 절약

- 누군가가 당신도 모르는 사이에 당신의 사진을 업로드했을 때 알려줍니다.

위험:

- 세계 최대의 광고 기술 회사가 웹상의 사진이나 동영상에서 당신을 영원히 찾을 수 있습니다.

- Facebook은 업로드된 모든 사진을 자동으로 스캔, 분석 및 분류합니다.

- 피하고 싶은 사진에 자동으로 태그가 지정됩니다.

- 특히 매우 밝거나 매우 어두운 피부를 가진 사람들을 위한 오류

증거:

특히 일부 사용자의 경우 이 기능이 기본적으로 켜져 있기 때문에 디스토피아에 가깝습니다(끄는 방법은 다음과 같습니다:

https://www.cnet.com/news/neons-ceo-explains-artificial-humans-to-me -그리고-나는-그 어느 때보 다 혼란 스럽습니다 / ). 가능성이 위험을 능가하는지 여부를 결정하는 것은 귀하에게 맡기겠습니다.

자동화된 국경 통제(전자여권 게이트)

전자 게이트 또는 전자 여권 게이트라고도 하는 자동 국경 통제(ABC) 시스템 은 일종의 확인 절차인 신분 문서에 대해 여행자를 인증하는 셀프 서비스 시스템입니다 .

잠재력:

- 항공여행 증가에 따른 혼잡 해소 방안으로 제안

- 중앙 데이터베이스가 아닌 여권과 일치시키므로 이론상 데이터가 저장되지 않습니다.

위험:

- 사용할 수 없거나 사용하지 않으려는 사람들을 위해 더 긴 대기열

- 전반적으로 시간을 절약한다는 증거 부족

- 고령 승객이 이용하기 어려움

- 이민 문제 또는 세금 문제를 일으킬 수 있음

- 얼굴 인식 정상화

- 유색인종에게 불균형적으로 오류가 발생하기 쉬우며 부당한 심문으로 이어짐

- 국가 긴축 조치 지원

증거:

- 통계는 매우 다양하지만 신뢰할 수 있는 소식통에 따르면 국경 경비대가 여행자를 처리하는 데 평균 10초가 소요되며 , 이는 10-15초가 소요되는 최고의 게이트보다 빠릅니다.

- 행동을 예측하기 위해 다른 데이터와 함께 사용 되기 시작

- 높은 볼륨 인간의 개입의 사용자 또는 시스템 오류로 인해 필요

- 5% 의 사람들이 거짓으로 거부 된 지연 연장

- 무고한 사람들을 허위로 범죄화한 증거

- 잘못된 여권을 소지한 사람 을 허위로 접수한 증거

효과에 대한 증거는 모순될 수 있지만, 특히 이미 소외된 그룹에 미치는 영향과 얼굴 데이터를 다른 데이터와 결합하여 여행자에 대한 추가 정보를 유도하는 능력은 남용의 주요 가능성을 내포하고 있습니다. 우리는 더 많은 국경 요원에게 자금을 지원하고 대기열 관리에 투자하는 것과 같은 오프라인 솔루션이 똑같이 효율적이고 덜 침습적일 수 있다고 생각합니다.

경찰 감시

얼굴 감시 라고도 하는 유럽 전역의 경찰은 종종 민간 기업 과 협력하여 공공 장소에서 감시 카메라를 사용하여 실시간 식별 을 수행하고 있습니다.

잠재력:

- 조사에서 비디오 녹화물의 분석을 용이하게 합니다

위험:

- 경찰은 얼굴 데이터베이스를 보유하고 스캔한 모든 개인을 추적하고 추적할 수 있습니다.

- 경찰 모집 및 훈련에 대한 투자를 대체합니다.

- 공공 장소의 사용을 방해할 수 있습니다. 특히 불균형적인 타겟팅으로 고통받는 사람들

- 민주적 참여의 중요한 부분인 언론과 집회의 자유에 대한 오싹한 효과

- 유사 과학적 감정 "인식"에 의존할 수도 있음

- 잘못 식별된 사람들에 대한 법적 영향

- 선택 해제 기능 없음

증거:

- 영국 경찰은 얼굴 인식이 예산 삭감을 만회하는 데 도움이 된다고 말했습니다

- 감시의 효과를 입증하는 것은 거의 불가능 합니다.

- 법 집행 기관 의 데이터 액세스 남용 증거

- 기존 경찰 편향 및 인종 프로파일링 자동화

- 합법적인 익명 시위를 불가능 하게 만듭니다.

- 개인 정보 보호 권리를 침해하여 우리를 덜 자유롭게 만듭니다.

불평등이나 반사회적 행동과 같은 문제를 해결하거나 일반적으로 감시 기술보다는 경찰 능력에 투자함으로써 공공 보안을 높일 수 있습니다.

현실을 직시: 대량 감시 사회로?

개입 없이 안면 인식은 전지전능한 길을 가고 있습니다. 이 게시물에서는 표면만 긁었습니다. 그러나 이러한 예에서는 얼굴 데이터를 수집 및 분석하려는 다양한 행위자, 이 데이터에서 얻는 것, (ab) 사용 방법을 식별합니다. 그들은 또한 안면 감시의 이점 이 사용자의 이점이 아니라 종종 비용 절감의 이유 임을 보여 주었습니다.

우리는 그것을 전에 말한 : 기술 중립이 아니다. 그것은 제작자의 편견과 세계관을 반영하고 강화합니다. 큰 그림이나 권위주의에 대한 미끄러운 기울기를 고려하지 않고 시스템이 빠르게 배포되면 위험이 증폭됩니다. 각 사용 이면의 동기를 면밀히 조사하고 배포 전에 적절한 평가를 수행해야 합니다. 시민으로서 이것을 요구하는 것은 우리의 권리입니다.

당신의 얼굴은 외모 이상의 의미가 있습니다. 그것은 당신의 독특한 정체성과 개성을 나타내는 지표입니다. 그러나 많은 얼굴 인식으로 인해 당신의 얼굴은 당신에게 불리하게 활용될 수 있는 데이터 포인트의 모음이 되며 안전하고 사생활 보호를 받으며 삶을 살아가는 능력을 침해합니다. 회사가 사용자의 사진을 사용하여 은밀하게 구축한 알고리즘으로 이익을 얻으면서 얼굴은 말 그대로 상품화되고 거래됩니다. 이것은 우리의 사생활, 존엄성 및 신체 무결성에 심각한 영향을 미칩니다.

6,000만 국민의 생체 데이터베이스 구축?··· 프랑스 정부 계획 논란

Peter Sayer | IDG News Service

프랑스 정부가 두 개의 파일을 병합해 6,000만 명에 달하는 프랑스 국민들의 생체 정보가 포함된 메가데이터베이스를 만든다는 계획을 지난 주말 휴일을 틈타 조용히 발표했다. 논란을 피하고자 하는 의도가 다분했지만 생각대로 되지 않았다.

프랑스 디지털 및 혁신부 장관, 그리고 정부가 디지털 기술이 사회와 경제에 미치는 영향과 관련해 독립적인 제안을 구하기 위해 만든 기구인 프랑스 디지털 위원회(National Digital Council)도 프랑스 정부의 이 같은 움직임을 비판하고 나섰다.

악셀 르메어 장관은 프랑스 언론에 메가데이터베이스가 10년이 넘은 기술을 사용하며 실질적인 보안 문제를 갖고 있다고 지적했다. 이 위원회는 TES(프랑스어로 '보안 전자 신원 문서'의 약어)를 만들게 되면 오남용으로 이어질 것이고 이런 사태는 "용납할 수 없지만 필연적으로 일어날 일"이라고 주장했다.

TES는 생체 여권을 만드는 데 사용되는 기존 데이터베이스를 대대적으로 확장한 것이다. 프랑스 정부는 이를 프랑스 신분증을 소지한 사람들의 일반(비생체) 데이터베이스와 병합할 계획이다.

이런 은밀한 데이터베이스 개발이 대중의 격렬한 반대에 직면한 사례는 처음이 아니다. 프랑스는 전에도 여러 번 이런 상황을 겪은 바 있다.

1973년 프랑스 정부는 비밀리에 사파리(SAFARI) 프로젝트에 착수했다. 사파리는 고유 번호로 모든 국민들을 식별하고, 이 번호를 사용해 다양한 데이터베이스에 저장된 국민에 대한 모든 정보를 상호 연결하기 위한 프로젝트였다.

1974년 3월 21일 르몽드가 사파리의 존재를 폭로한 이후 거센 반발이 일어났고 그 결과 1978년 개인 식별 정보의 저장과 처리를 제한하는 컴퓨팅 및 자유에 관한 법이 제정돼 현재까지 시행되고 있다. 초기 타겟 마케팅의 예로, 이러한 정부 감시 행태에 대한 르몽드 기사 옆에는 카메라 줌렌즈와 복사기 광고가 있었다.

사파리에 대해 프랑스인들이 이처럼 큰 반감을 드러낸 이유는 과거 나치의 프랑스 점령 당시 비시 정권이 유태인과 외국인을 가려내기 위해 국가 신원 데이터베이스를 사용한 전력이 있기 때문이다.

국립 과학 연구 센터(National Center for Scientific Research)가 작성한 이 프로젝트의 역사에 따르면, 프랑스 국민들은 이와 같은 정권이 다시 들어설 경우 이미 만들어져 있는 국가 신원 데이터베이스가 반인륜적 범죄를 부추기는 수단이 될 수 있음을 우려했다.

2008년 프랑스 정부는 또다시 에드비주(EDVIGE)라는 프로젝트를 추진했다.

이 프로젝트 역시 개인의 성별과 인종, 건강에 관한 세부 정보를 데이터베이스에 기록한다는 계획으로 물의를 빚었다. 이 데이터베이스는 범죄자와 잠재적 범죄자, 그리고 과거와 현재의 선출직 공무원과 미래의 잠재적 선출직 공무원으로 구성된 데이터베이스인데, 사실상 거의 프랑스 전국민이 이러한 범주에 포함될 수 있다.

프랑스 정부는 처음에는 내용을 수정했다가 이후 에드비주 계획 자체를 철회했다.

그런데 파리에서 열린 정부 파트너십(Open Government Partnership) 회담을 앞둔 시점에 똑 같은 계획이 또 다시 드러난 것이다. 프랑스 디지털 위원회가 가장 우려하는 부분은 정부가 중앙집중식 아키텍처를 사용해 전국민의 생체 정보를 저장하기로 했다는 점이다. 이는 사이버 범죄자와 적대적 활동 세력 관점에서 탐나는 목표물이 될 수 있다.

미국은 이런 시스템의 위험성을 이미 경험했다. 2015년 미국 인사국(Office of Personnel Management)은 데이터베이스에 저장된 420만 명 정부 직원들의 정보가 해커에게 노출됐으며, 그동안 현재, 과거, 또는 잠재적 정부 직원으로 분류되는 2,150만 명의 사람들이 배경 조사를 받고 있었음이 드러났다.

그러나 위원회는 자유에 대해서도 우려한다.

이 위원회는 "역사적으로 이런 데이터베이스가 만들어지면 이 데이터베이스의 운용 방식이 합법적이든 불법적이든 결국은 그 사용 범위가 원래의 목적에서 점차 확대되어 개인 정보 침해로 이어졌다. 프랑스는 예외라고 생각한다면 역사의 교훈을 무시하는 것이다. 유럽과 미국에서 포퓰리즘의 부상을 보면 미래를 건 그러한 도박은 불합리한 처사다"라고 지적했다.

프랑스 디지털 위원회는 보안 측면에서 이 데이터베이스가 미칠 모든 영향이 파악될 때까지 데이터베이스 제작을 유예할 것을 프랑스 정부에 촉구했다.